Romila Thapar’s ‘History of India’, published in 1966 begins with:

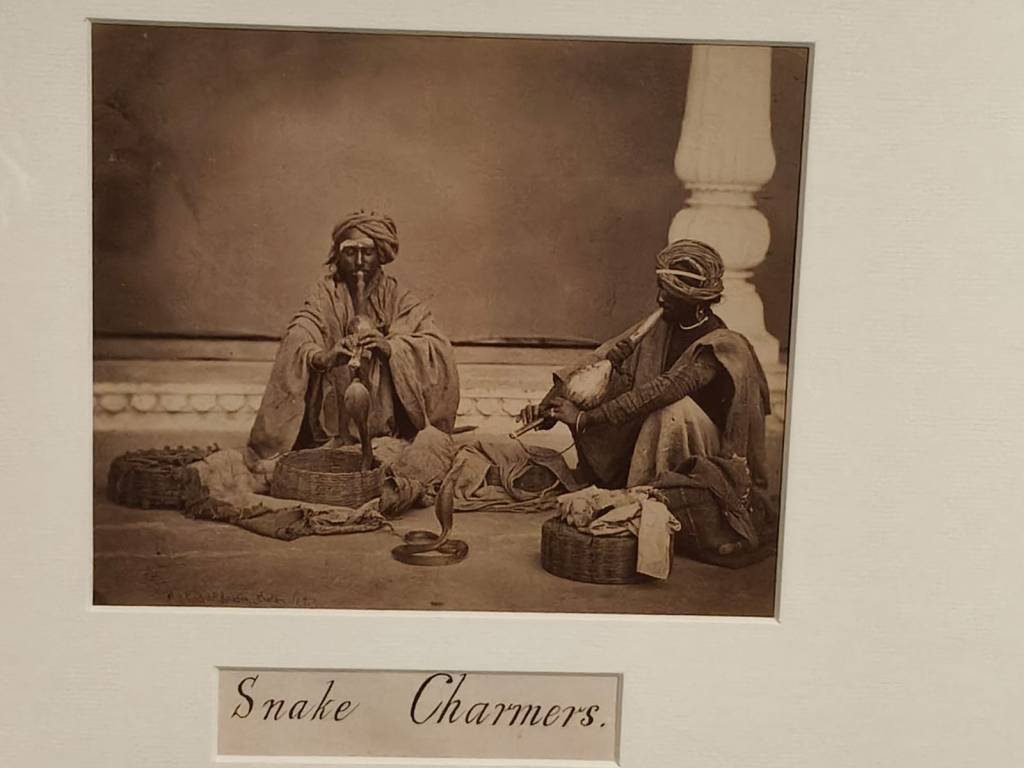

For many Europeans, India evoked a picture of Maharajas, snake-charmers, and the rope-trick. This has lent both allure and romanticism to things Indian.

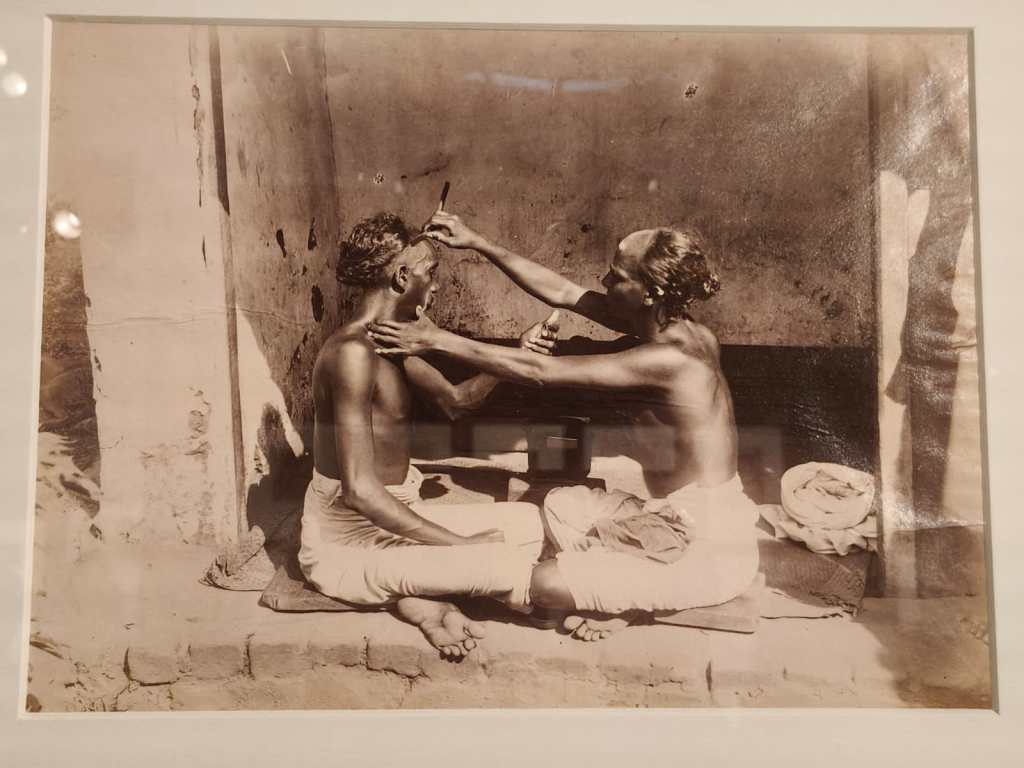

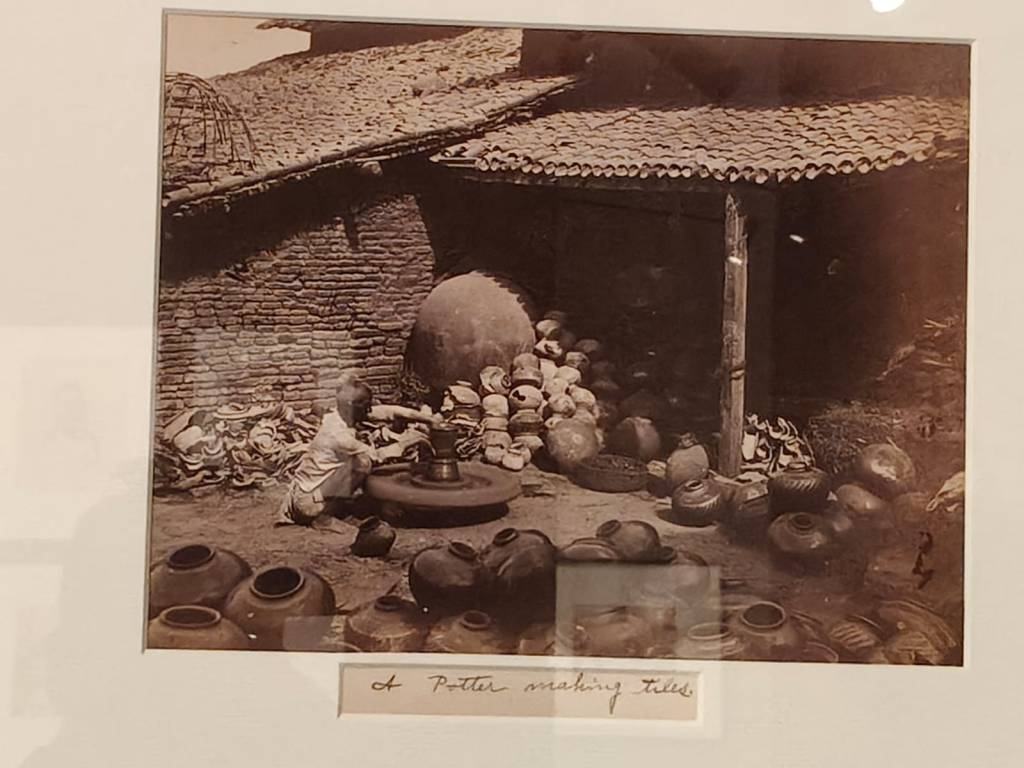

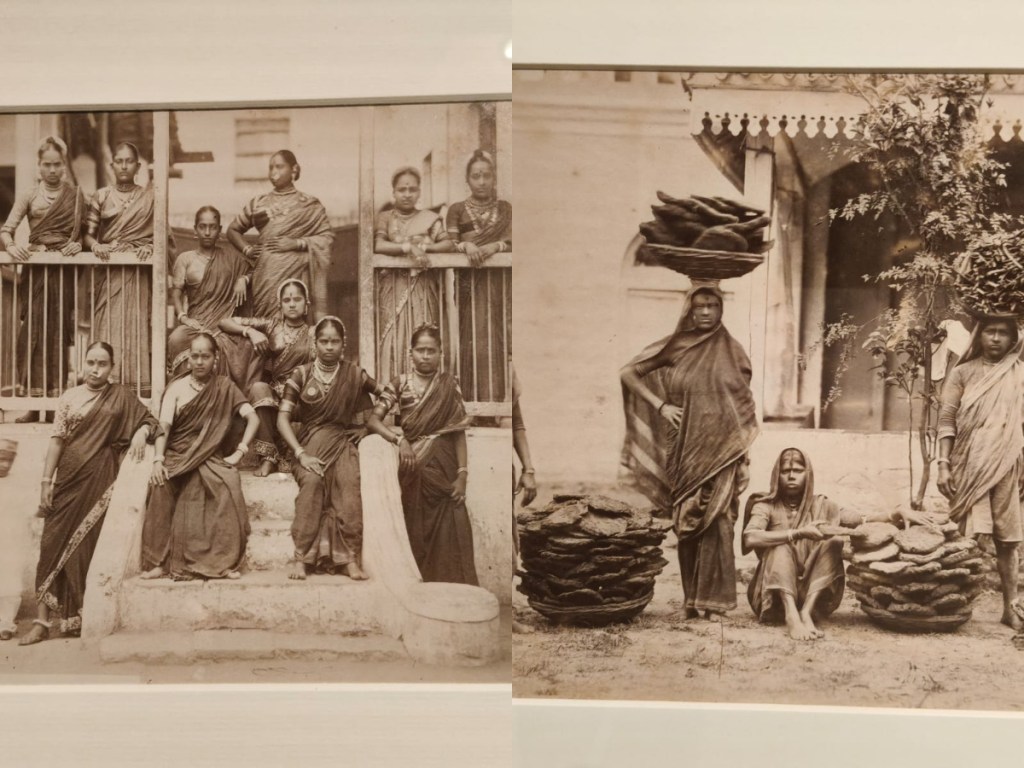

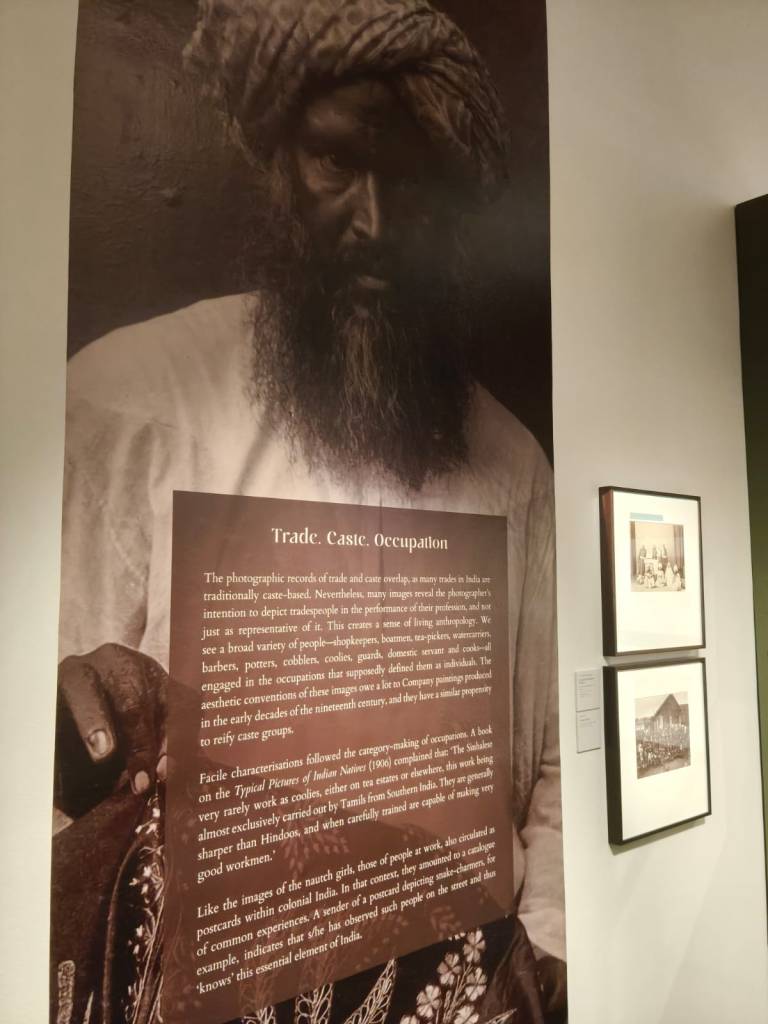

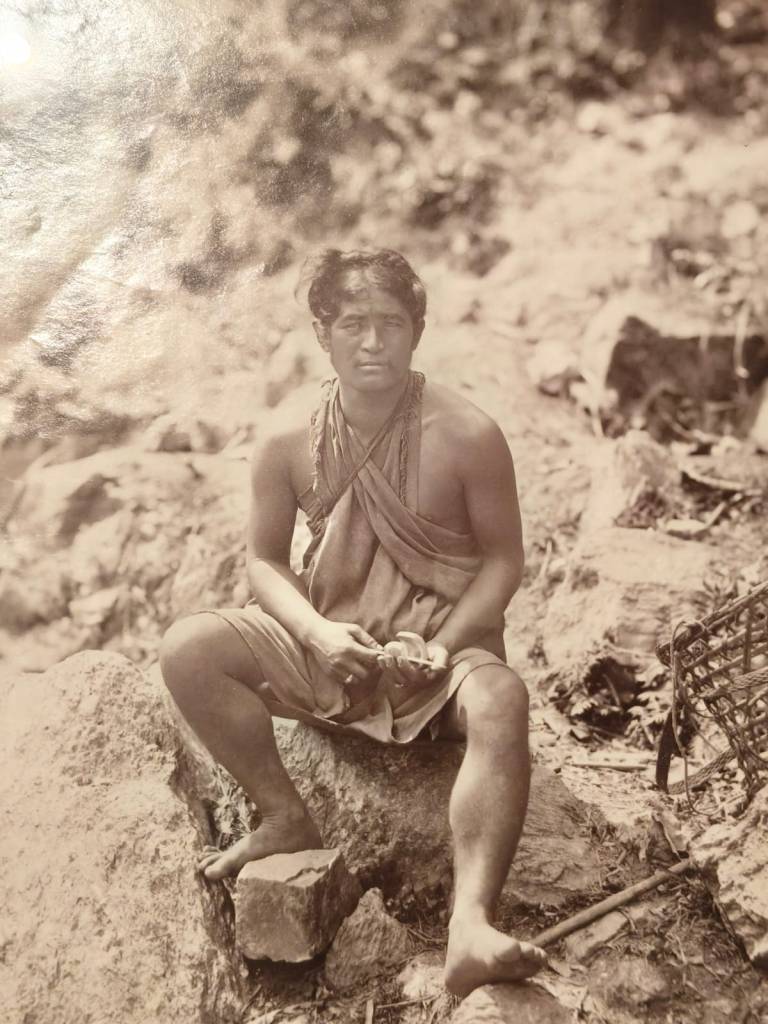

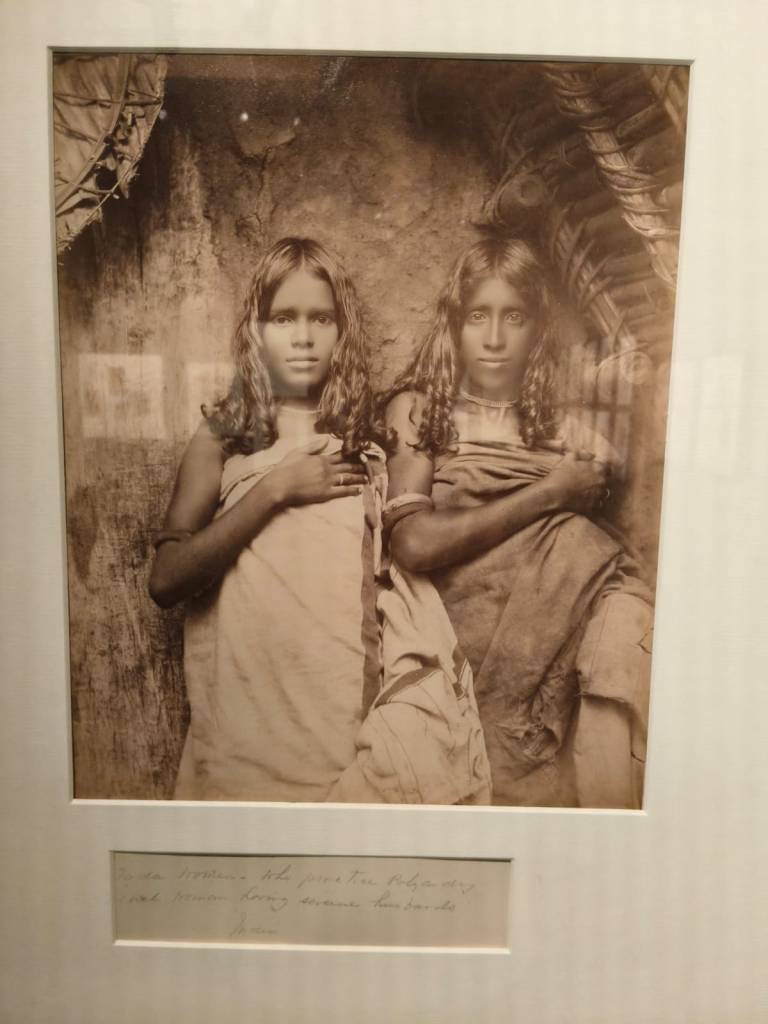

The introduction of photography in India in the 1840s coincided with a critical phase of British colonial expansion and consolidation. What emerged was not merely a technological innovation but a powerful instrument of imperial knowledge production. By systematically deploying the camera, British administrators and ethnographers created an elaborate visual taxonomy of Indian society that would shape both colonial governance and Western perceptions of India for generations to come. It was through photography and its mass circulation that India came to be known as a land of snake charmers, fakirs, and magicians.

One of the defining features of photography of this school was having the subjects pose in rigid formats: front and profile views, occupational tools in hand and the geographical features of the landscape in the backdrop. The intention was not artistic portraiture but typology. Individuals were treated as specimens representing a category rather than as persons. Fluid social identities were thus converted into rigid visual labels.

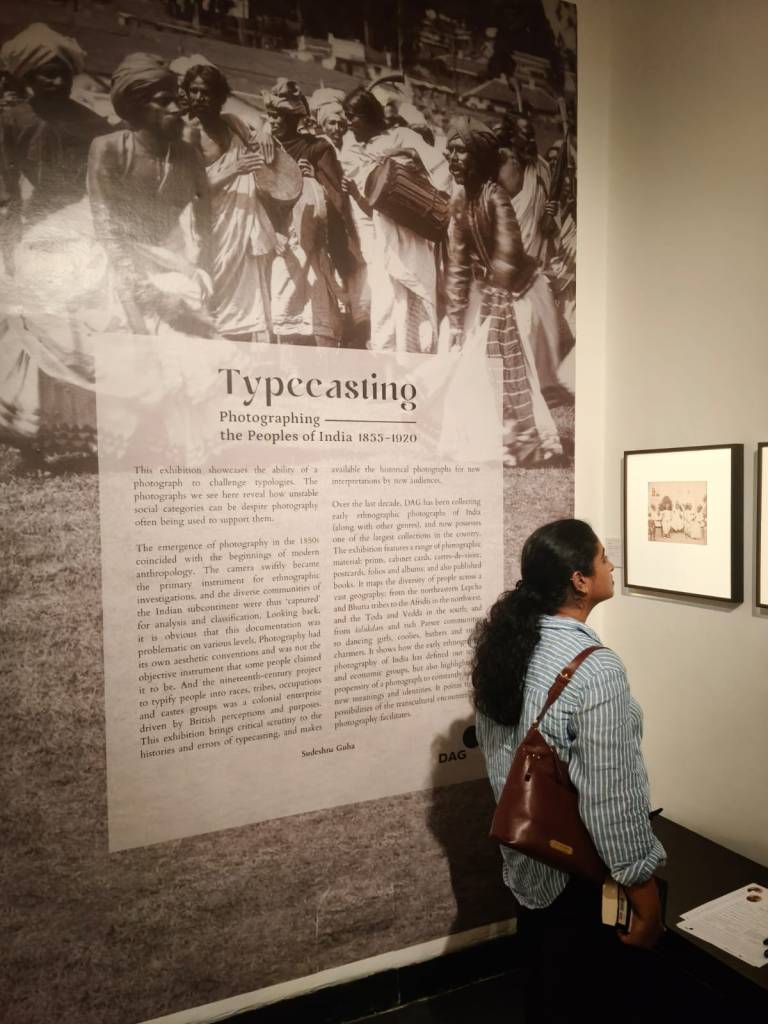

DAG which has one India’s largest collection of early ethnographic photographs of India has mounted a superb exhibition titled ‘Typecasting: Photographing the Peoples of India, 1855-1920‘, at the Bikaner House in Delhi. It ends tomorrow. Sruthi and I dropped by this afternoon and managed to join the exhibition walkthrough in which Sudeshna Guha provided a detailed overview of the politics of early photography in India.

Couldn’t help but marvel at the diversity of our land, it’s complex history and the politics of interpreting it all.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.