I embarrassingly realised that I knew next to nothing about the workings of the District judicial system in India until I picked up Prashant Reddy Thikkavarapu’s and Chitrakshi Jain’s ‘Tareekh Pe Justice’ – Reforms for India’s District Courts’. I came across their work when I saw it featured in the Ideas for India podcast.

Article 235 of the Indian constitution says:

The control over district courts and courts subordinate thereto including the posting and promotion of, and the grant of leave to, persons belonging to the judicial service of a State and holding any post inferior to the post of district judge shall be vested in the High Court

In reality what this means is that while the district courts of India enjoy protection from executive retaliation, they are often at the total mercy of the whims and fancies of the High Courts of India. Unlike judges of the High Court and Supreme Court, district judges do not enjoy immunity for judicial decisions. (Impeaching a HC or SC judge is a herculean task to make them immune from interference). Errors in judgment, meant to be corrected by appellate courts, often trigger disciplinary inquiries. This in turn creates a sense of insecurity amongst the judges, undermining decisional independence

Between 2018 and 2023, just five High Courts initiated nearly 200 disciplinary inquiries against district judges. Granting of bail is often one of the most cited reasons for triggering judicial scrutiny. Adverse entries in the Annual Confidential Reports (ACR) can stall promotions or lead to compulsory retirement. This in turn results in a chilling-effect on the district judiciary where anything considered too hot to handle is just brushed away or delayed.

District judges in India are routinely transferred not only between districts but also between civil and criminal portfolios within the same district. This constant churn creates what can be described as revolving dockets, where judges rarely retain a case long enough to see complex matters through from start to finish. As a result, difficult cases are repeatedly inherited, partially heard, and postponed, with no single judge having a long enough tenure or the incentive to see them resolved. This administrative practice has become one of the most significant yet under-discussed contributors to judicial delay in India.

Judges in the district judiciary are evaluated through a unit-based performance system that rewards the number of cases disposed of and the completion of procedural tasks, rather than sustained engagement with complex trials. To secure a “good” rating in their Annual Confidential Reports, judges are incentivized to prioritize simpler cases that can be quickly concluded and to defer or fragment more difficult or risky matters. When combined with frequent transfers, this evaluation framework actively discourages judges from investing the time and effort required to see complex cases through to completion.

The imbalance with the High Courts is also striking when it comes to issues like issuing a writ of habeas corpus. The district judiciary which possesses the authority to sentence a person to death or to life imprisonment after a full trial, lacks the power to issue something as elementary as a writ of habeas corpus directing the state to release a person held in illegal detention. In other words, the courts closest to citizens. those most likely to encounter unlawful arrests, routine remands, and everyday abuses of state power, are constitutionally denied to wield one of the most basic instruments of liberty.

On the entrance-exam mode for judicial appointments: Entry-level judicial officers in India are often appointed in their twenties, many with limited courtroom exposure and little life experience beyond law school or university. At the same time, strict upper age limits bar more experienced lawyers from entering the judicial service. This exclusion is difficult to justify in a profession that depends fundamentally on judgment, maturity, and lived experience rather than physical endurance or youth.

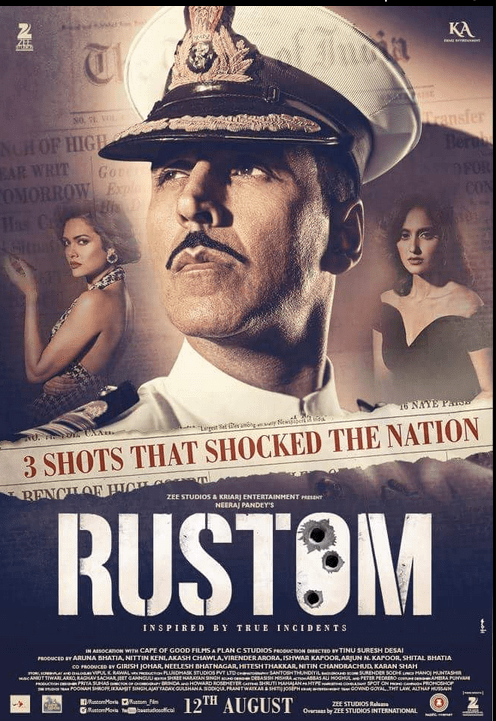

The book had a chapter on the need to consider bringing back the jury system. Apparently, the Nanavati case (which inspired the Akshay Kumar movie Rustom) was decided by a jury. When our governments are enthusiastic of Village-level Nyaya Panchayats (imagine!), why must there a reluctance to bring in the jury system at the district courts?

From now on, if I ever come across a District Judge’s vehicle, it’s only going to evoke sympathy in me.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.