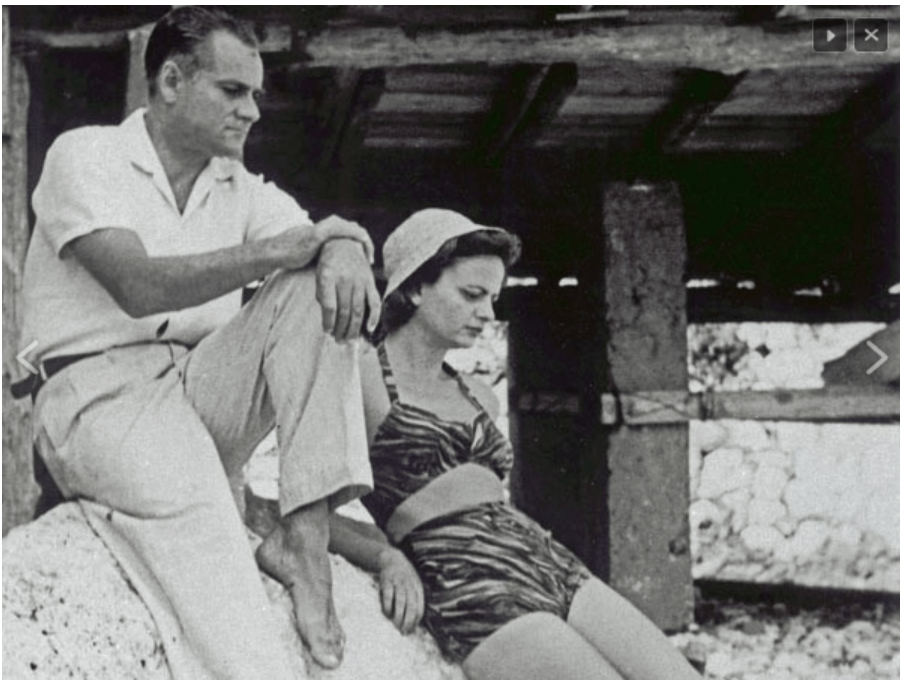

As I wrote last month, Alberto Moravia was the literary discovery of 2025 for me. His wife Elsa Morante was also a celebrated writer best known for her novels ‘Arturo’s Island’ and ‘History’. Their marriage was a stormy affair (literary icons you see), and Moravia himself had at one point confessed:

There were days when I wanted to kill her. Not to split up, which would have been the reasonable solution, but to kill her, because our relationship was so intimate and so complex and in the end so vital that murder seemed easier than separation

Carmela Ciuraru’s ‘Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages’ had a chapter dedicated to the Moravia-Morante relationship. Their travails during the Second World War were harrowing to read about. After Mussolini fell, Rome was occupied by the Germans for a period of nine months. And during this period, true to form, the Nazis went after the Jews. Moravia and Morante were on the run and ended up in the south of Italy, holed up in a tiny one-room hut owned by a peasant. For nine months they lived in it, hoping that the tide would turn and the Allies would triumph.

Inside, you could barely turn around. There was a big bed, made of two iron supports and three planks, and on the planks a sack filled with cornshucks, which creaked and shifted every time I moved. On this cornshuck mattress there were two sheets, one beneath and one above, of rough handwoven linen. There were no blankets. . . . But the room was so small and we were so close when we slept that I never suffered the cold. There was no flooring, just packed earth. When it rained the water came in and I stood with my feet in the water. For nine months I sat on the bed; we didn’t have a chair.

Their flat in Rome must have seemed like a palace in comparison. Now Alberto and Elsa had nothing to do but wait in their hut for life to change. They brought two books, The Brothers Karamazov and the Bible, but had no pens. “Lacking toilet paper,” Alberto recalled, “we used the pages of Dostoyevsky.” One day was the same as the next. Hunger, boredom, cold, and filth defined their lives now. They might have a piece of bread in the morning, and each afternoon around five, in the hut of a peasant family, they had their only meal of the day—typically a pot of boiled beans steeped with bread. (Food became more scarce over time.) With no light in their “pigsty in the mountains,” as Alberto called their hiding place, in the evenings they simply sat in the dark. Each morning, Alberto would drop a bucket to the bottom of a well, filling it with icy water, which Elsa used to wash herself daily, while he did so once a week. A few times, the monotony was disrupted by “dogfights in the sky” between the Germans and the English, Alberto recalled. Their wartime experience would inspire his 1957 novel La ciociara (Two Women), chronicling a widowed mother and her teenage daughter as they endure the horrors of the war. The novel was adapted into a film a few years later by the neorealist director Vittorio De Sica, for which Sophia Loren won an Academy Award for Best Actress.

How do people manage to live full lives after such experiences?

Moravia’s childhood, too, was marked by hardship. Diagnosed with tuberculosis of the bone at the age of nine, he spent much of his life until eighteen in enforced solitude. That long isolation, however, sharpened his clarity of thought and honed his remarkable powers of observation.

“you must keep in mind that I was ill in infancy, and because of it I was alone, completely alone, until I was 18. I never went to school. I never had other children to play with. Solitude entered my soul so deeply that even today I feel a profound detachment from others.” He filled his days by reading Dostoyevsky, Shakespeare, Dante, Molière, Rimbaud, and many others. ….

Probably because of my long isolation due to my illness, most of the time my head is completely empty,” Alberto said. “I’m in a state of contemplation or, if you prefer, of totally spontaneous distraction.”

It takes someone who has experienced solitude in his bones to write lines like these:

This flower had grown in the shaded tangle of the underbrush, thought Marcello, in the little bit of earth clinging to the barren tuff; it had not sought to limit the taller, stronger plants or to recognize its own destiny so that it could accept it or reject it. In full unconsciousness and freedom, it had grown where the seed had happened to fall, up until the day he had picked it. To be like that solitary flower on a strip of moss in the dark underbrush, he thought, was a truly humble, natural destiny. Whereas the voluntary humility of an impossible adaptation to a deceptive normality concealed only vanity, pride, self-love reversed.

‘An impossible adaptation to a deceptive normality’! Few phrases so neatly capture the hidden fractures in countless relationships.

Moravia and Morante were intellectual companions but their marriage was devoid of intimacy. His novel Contempt which was adapted by Goddard captures a bit of the dynamics of his own marriage. Despite later living apart, they never divorced though they did have other lovers.

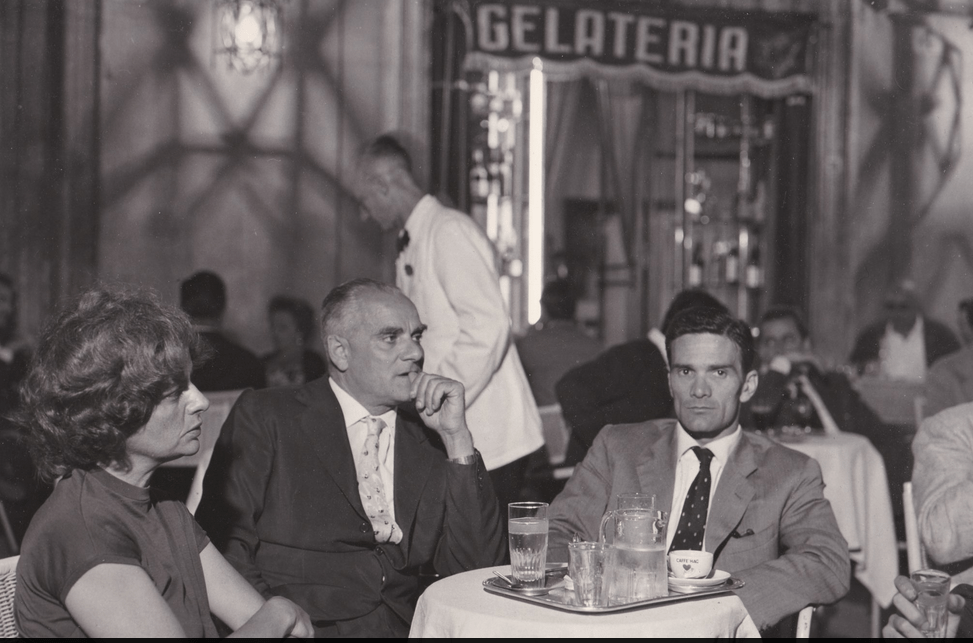

The homosexual director and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini was also a close friend of Morante. He accompanied the couple to India in 1960 and their visit included meetings with Nehru, Mother Teresa and Nirad C. Chaudhuri. Both Pasolini and Moravia wrote about their experience in India in their travel books L’odore dell’India (The smell of India) and Un’idea dell’India (One idea of India). (Pasolini was later murdered in 1975, at the age of fifty-three. His mutilated corpse was discovered on a deserted beach that was a favorite cruising spot. The autopsy revealed that among other gruesome acts, Pasolini had been beaten with a plank studded with nails, then run over by his own Alfa Romeo. The case was never solved.). Moravia’s ‘Idea of India’ begins with this imaginary dialogue:

‘So you were in India. Did you have fun?

No.

Did you get bored?

Not even that.

What happened to you in India?

I had an experience.

What experience?

The experience of India.

And what is the experience of India all

about?I feel it, that’s all. You should feel it too.

The book is unavailable in English but a kind soul has published chapter-by-chapter translations of the work on Reddit.

And finally, it’s believed that the pseudonym adopted by the great Elena Ferrante who wrote the Neapolitan Quartet, was inspired by Elisa Morante (Elsa/Elena, Morante/Ferrante).

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “The Moravia–Morante Marriage”