If there’s one unmistakable feature of our society today, it should be the falling birth rates. Unlike the generation of our parents, its quite common today to come across couples who have voluntarily decided to not have kids. Having a first baby in your 30s is common. And anyone having more than two children are often ridiculed. I’ve never been bothered about this phenomenon as falling birth rates are a natural corollary of improved gender outcomes. As female literacy improves and more and more women enter the work force, birth rates fall. And that’s a good thing. At least that’s what I assumed.

Dean Spears and Michael Geruso’s in ‘After the Spike Population, Progress, and the Case for People’ argue that the falling fertility rates globally should be a cause for concern for humanity and they debunk many population myths with gusto.

In 2012, 146 million children were born. Since then the number of children born annually has been falling which means that 2012 ‘may well turn out to be the year in which the most humans were ever born—ever as in ever for as long as humanity exists’..

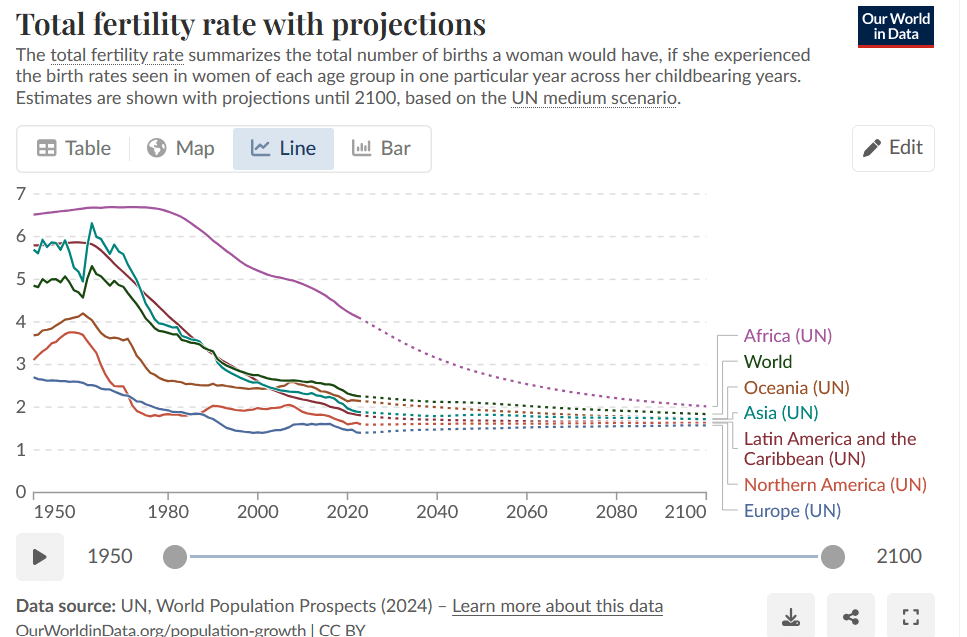

The Total fertility rate (TFR), which measures the average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime is the key metric in demographics. A TFR of 2.1 ensures that existing populations get replaced. While the global TFR is at around 2.25, this has been on the decline. If the global fertility rate falls to around 1.5, the math gets, interesting. Or should I say alarming:

Now imagine that, counting the whole world together, the fertility rate was 1.5 and stayed that way for generations. How quickly would the planet shrink? Start from 2025, when about 132 million babies will be born worldwide, about 66 million of them girls. Let’s assume that they will all survive childhood, because it won’t be so many more decades until almost all of them will. If, as adults, these 66 million women have 1.5 children (0.75 girls) on average, then they will have 50 million daughters (and 50 million sons). When that generation of daughters grows up, some to be mothers and some not to be mothers, they will have 37 million daughters of their own, who will in turn grow up to have 28 million. Now do that exercise again in the next generation, and the next and the next and the next. Pretty soon, that compounding adds up. Or, rather, subtracts. After seven generations, there would be 9 million girls born (and 9 million boys), in total, across the globe: 13 percent of the starting population. In another seven generations, about 1 million. In another seven, it would be 160,000 girls born worldwide each year. That is far fewer than were born this year in Texas. It’s a little less than the number of girls estimated to have been born each year ten thousand years ago. The global population would have withered.

In short, there would be just 160,000 girls born in the entire planet within 21 generations! This becomes all the more stark since already, two-thirds of people alive today live in a country with birth rates below the replacement rates.

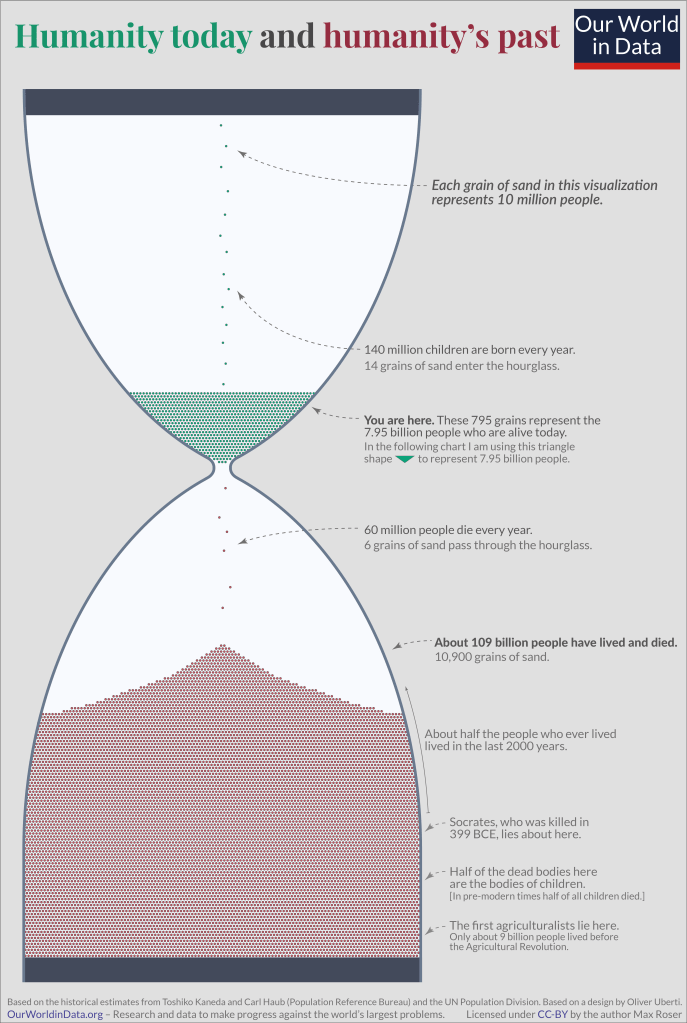

Including the 8 billion people alive today, around 120 billion birth have happened since the beginning of humanity. With global fertility rates plummeting, fewer than 150 billion births would ever happen.

The book also explores why having more people on the earth, contrary to popular opinion, is not a bad thing for the planet and climate change. As this Guardian review puts it:

In fact, climate change is such an urgent issue that depopulation will kick in far too late to make any serious impact. Not only that, but the difference between the contribution to climate change made by the current population versus the population at the top of the spike is not significant. Depopulation won’t help the climate, then, but it will mean that there are far fewer of us left to deal with part two of cleaning up humanity’s mess on Earth: removing excess greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Creating a good life – whether that’s finding cures for disease or ways to reverse environmental damage – relies on the ideas, work and progress produced by large, interconnected societies.

To maintain a global population —even one that is tiny and stable – calls for the the same math: For every two adults, there must be about two children, generation after generation.

And here lies the crux of the issue. Bringing children into the world and raising them puts a disproportionate load on the mothers. Despite all the pro-family strategies adopted by different countries fertility rates barely budge from the long term trends. What is required is a total overhaul of the mode of child care across societies

These big trends—lower birth rates over time, better lives for women over time—threaten a big dilemma. Would stabilizing the population with an average birth rate of two require progress toward gender equity to halt or reverse? Do fairer societies only emerge as birth rates fall from 2.0 to 1.8 and from 1.5 to 1.3? Must stabilization come at the cost of never achieving equity—in the workplace, in the home, in politics, in cultural power?

And finally, this sledgehammer of a fact:

No country, in any year, on any continent, with an average age at first birth above thirty has ever had a total fertility rate high enough to stabilize the population. S

So countries across the world should gear up to encourage young couples to have more children and our societies must adapt to become kinder to young parents. The future of humanity calls for it.

Postsctipt:

1) Population Ethics is also a lens to use when discussing human extinction and Parfit’s Repugnant Conclusion is the most important argument made for having a world with more people. Parfit argued that if we care about total human wellbeing, then a world with vastly more people living lives that are modest but still worth living could, in total, be better than a world with far fewer people living exceptionally rich lives. (An earlier post on Parfit)

2) All this discussion on fertility should also remind us of the high infant mortality rates in many parts of the world and the improvements required to increase the lifespan in most parts of the world.

3) I finally understand why Elon Musk proudly flaunts the fact that he has 14 kids. (One of them is named Sekhar – after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar!)

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Fertility Rates, Gender Equality and the Math of Human Extinction”