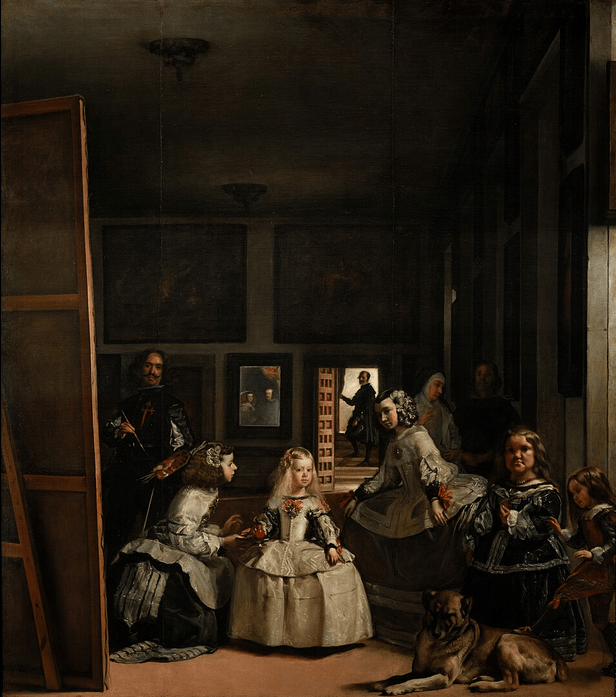

Velasquez’s ‘Las Meninas‘ – one of the most analyzed paintings in all of art history makes an appearance in Samantha Harvey’s Booker-shortlisted ‘Orbital‘. The painting as we know is a complex take on reality, perception, reflection and interpretation. Velázquez places himself within the scene as the painter, yet the true subject of his canvas remains deliberately ambiguous. Many have argued that he is painting the royal couple, whose faint presence is revealed only through their reflection in the mirror, implicating us, the viewer, in the very act of seeing. All the others in the painting are caught in the act of reacting to something that has just transpired.

On the multiple subjects in the painting – Velasquez, the royal couple,, the infant daughter, the dwarf, the handmaidens, the royal courtier, Harvey wonders:

Or, is the subject art itself (which is a set of illusions and tricks and artifices within life), or life itself (which is a set of illusions and tricks and artifices within a consciousness that is trying to understand life through perceptions and dreams and art)?

And then, she draws our attention to the often-ignored character, the dog:

What is the subject of the painting? his wife has written on the postcard’s reverse. Who is looking at whom? The painter at the king and queen; the king and queen at themselves in a mirror; the viewer at the king and queen in the mirror; the viewer at the painter; the painter at the viewer, the viewer at the princess, the viewer at the ladies-in-waiting? Welcome to the labyrinth of mirrors that is human life. Is your wife always so obsessed with petty small-talk? Pietro asks. And Shaun replies: I’m telling you, it’s relentless. Pietro stares for a while at the painting, and a while longer, then says, It’s the dog. Pardon? To answer your wife’s question, the subject of the painting is the dog. He looks then – when Pietro hands back the postcard, reaches across to squeeze the bony dome of Shaun’s shoulder before diving away – at the dog in the foreground. He’d never given it a second glance, but now he can’t look at anything else. It has its eyes closed. In a painting that’s all about looking and seeing, it’s the only living thing in the scene that isn’t looking anywhere, at anyone or anything. He sees now how large and handsome it is, and how prominent – and though it’s dozing there’s nothing slumped or dumb in that doze. Its paws are outstretched, its head erect and proud. This can’t be coincidental, he thinks, in so orchestrated and symbolic a scene, and it suddenly seems that Pietro is right, that he’s understood the painting, or that his comment has made Shaun see a different painting altogether to the one he’d seen before. Now he doesn’t see a painter or princess or dwarf or monarch, he sees a portrait of a dog. An animal surrounded by the strangeness of humans, all their odd cuffs and ruffles and silks and posturing, the mirrors and angles and viewpoints; all the ways they’ve tried not to be animals and how comical this is, when he looks at it now. And how the dog is the only thing in the painting that isn’t slightly laughable or trapped within a matrix of vanities. The only thing in the painting that could be called vaguely free.

A short take on the painting if you’re curious to know more about it:

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.