When we think of Nelson Mandela, we have this statesmanesque vision in our minds. A man who suffered incarceration for 27years and then emerged to lead and heal a country torn by Apartheid is always bound to evoke such imagery. Jonny Steinberg’s ‘Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage’ gave me a reality check of this image. Nelson was almost forty and married when he laid his eyes on the 20-something Winnie for the first time.

And so if there was any man in South Africa, hitting forty and married, who might turn his car around because he had glimpsed waiting at a bus stop a magnificent woman almost half his age, it was Nelson Mandela.

…. And so their second date, she discovered, was to take place at his boxing gym at the Donaldson Orlando Community Centre, less than two miles from his home, a space that doubled on weekend evenings as a theatre and music venue. She was to watch him while he laid into a punching bag and skipped and did push-ups, this big, imposing man, the sweat pouring off him, his body sculpted and fit. This was not a shy man. Neither of them ever said when they first slept together, but on this, their second date, he was preening, without shame, showing his body to her, displaying its sheer impressiveness.

Nelson was running a tremendously successful law practice in South Africa when he began to get involved with the African National Congress. The late 50s was also a period when decolonialization across the African continent peaked.

…on March 6, 1957, Kwame Nkrumah was sworn in as the prime minister of Ghana, the first British colony to acquire independence. The previous year, Morocco, Tunisia and Sudan acquired independence. Guinea would follow in 1958, Cameroon, Senegal, Togo, Mali, Madagascar and Congo in 1960. In Algeria, a country whose permanent white settlement made comparison to South Africa inevitable, a war for independence was raging.

And in faraway Cuba, a band of twelve men raised a guerilla army and kicked off the Cuban Revolution. All this was giving the ANC an infectious spur to the ANC’s own leadership. The ANC soon realized that independence from the White settlers would never happen through peaceful means. In what is considered as one their greatest strategic blunders, Mandela (and the ANC) decided to embark on an armed struggle. He went underground, toured the major countries of the continent and also took notes from the most celebrated resistance movement of the decade – the Algerian War of Independence.

Predictably, he ended up getting arrested and the rest as they say is history. He was sentenced to prison in June 1964 and ended up spending the next 27 years incarcerated. During this period, Winnie slowly became a parallel resistance figure – thanks to being his wife and due to the sheer power of her personality and also her sexuality.

Most arresting is the sheer number of norms she transgressed through the years. When her husband was on trial for his life, she took a married man who had a young family into her bed. When her public image was at its most sexualized, an object of shameless male desire, she imagined herself the leader of her people. When she was forty-four, she seduced a boy her daughters’ age and shared her life with him. When he left her, she ordered men with crowbars to break his bones. She flouted every rule of comportment expected of a woman in her position. And she did so with an aristocratic absence of reserve, rendering her the most singular, the most astonishing woman. Her most remarkable feature of all was her relation to her country.

and this:

By now, breathless stories of Winnie’s time in jail in 1969-70 were swirling through Security Branch ranks. It was said that when the head of the Security Branch, Hendrik van den Bergh, interrogated her, she came up close to him and straightened his tie; he was so thrown, the story went, that the questioning broke down. [28] As for Swanepoel, it was said that she slowly unbuttoned her shirt in his presence, eventually exposing most of her breast; he had left the room in embarrassment. There was clearly an erotic, perhaps sadistic, element to the Security Branch’s relationship with her, the punishment they heaped upon her no doubt driven in part by desire. The role they conjured her playing in the uprising – an older woman coaxing boys into acts of violence – seems pretty heated, pretty charged. In retrospect, there is something spooky about the police’s fabrications. A full decade later, a version of the Winnie they had invented took form in the real world. The football team of young men she’d establish in Soweto was horribly violent, and she was indeed their charismatic leader.

Now, during all of this, how did an obscure political prisoner end up becoming a world famous personality?

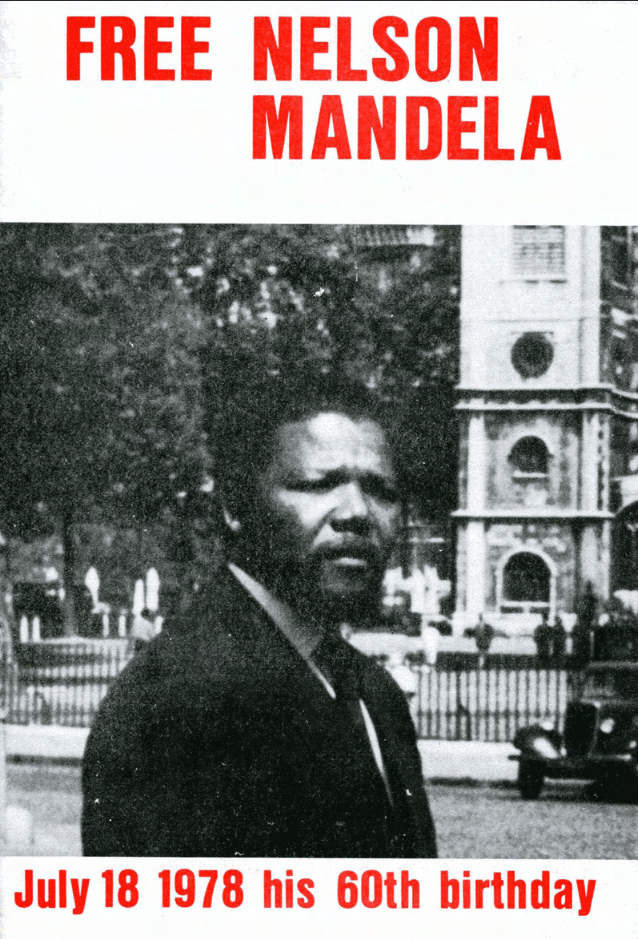

Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy, a committed Gandhian became the head of the UN’s ‘Special Committee Against Apartheid’. In addition to organizing seminars and conferences against apartheid, Reddy was also good with Comms. To commemorate Mandela’s 60th birthday, he initiated a global campaign asking school kids all over the world to wish Mandela ‘Happy Birthday’ by sending a postcard with Mandela’s picture to Robben Island. At the same time, the British premier, during the height of the IRA bombings, also wished Mandela Happy Birthday on the floor of the parliament. Steinberg captures this irony:

The idea of Nelson Mandela crossed a threshold at that moment. In the U.K. then, the Irish Republican Army’s bombing campaign had triggered fear on the British mainland; the notion of an armed struggle bore unpleasant connotations. Equally, at that time, no Labour prime minister would want to associate himself with a movement perceived to be a client of Soviet power. And yet here was a man in jail for waging a bombing campaign, a man whose army was funded from top to bottom by the Soviet Union. And the prime minister was wishing him a happy birthday from the seat of legislative power. Something had begun, just faintly observable for now: the lifting of Nelson Mandela above his context, indeed, above any particular context, and into an orbit of his own.

And for this seventieth birthday, six hundred million people around the world are believed to have watched the music concert organized at Webley Stadium. Mandela was firmly a global icon by now.

During all of this, Winnie, was leading a starkly contrarian life. In Soweto, she became associated with militant defiance that slid into brutality, most notoriously through the Mandela United Football Club which was basically a group of young men who acted less like protectors than an informal paramilitary force, implicated in kidnappings, beatings, and murders. These violent acts compounded by her openly acknowledged affairs during Nelson’s long incarceration, eroded her standing even among anti-apartheid allies.

A few days after his release from prison, Nelson goes to meet Nadine Gordimer – the future Nobel laureate.

Shortly after he was released, the South African novelist and future Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer received a message that Nelson Mandela wished to see her. She was flattered. They had known each other slightly before he was jailed and had been in touch sporadically since; he had written generously to her about one of her novels, Burger’s Daughter, which he had read in prison. ‘We were alone in Johannesburg some few days later,’ Gordimer recalled. ‘It was not about my book that he spoke, but about his discovering, on the first day of his freedom, that Winnie Mandela had a lover.’ [5] Nelson had in fact been told of Winnie’s lover during his final months in prison; he had written to her demanding that she get ‘that boy’ out of the house. [6] His name was Dali Mpofu, a prominent student activist and a trainee lawyer. He was also two generations younger than Nelson; his time on this earth coincided, almost exactly, with Nelson’s time in prison.

In 1993, Nelson was jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with F. W. de Klerk, the last White President of South Africa. De Klerk was widely regarded for his unbanning of the ANC and for facilitating multi-racial elections in South Africa.

But Mandela’s relationship with him wasn’t smooth and their relationship ended during a dinner in Stockholm during the award ceremony:

Two years later, he attacked De Klerk viciously again, this time at a dinner in Stockholm following their joint award of the Nobel Peace Prize. The prime minister of Sweden hosted the event; it was attended by about 150 people, including several Nobel laureates. De Klerk spoke first that night, his speech, as befitting the occasion, brief and pro forma. As he was closing, he said something innocuous on the face of it: both sides had made mistakes, he remarked; there was plenty of blame to go around. When Nelson got up to speak, his face was grey with rage. ‘Everyone, including me, was actually shocked by what Mandela said quite unexpectedly,’ George Bizos recollected. ‘He gave the most horrible detail of what had happened to prisoners on Robben Island, including the burying of a man with his head sticking out and [warders] urinating on him.’ He did not so much as mention De Klerk, but his obvious intent was to throw scorn on his Nobel Prize. ‘This had a terrible effect on De Klerk,’ Bizos recalled. He sent an emissary, his foreign minister, Pik Botha, to tell Bizos that if Nelson ever did anything like that again, he would respond in kind. ‘To my knowledge,’ Bizos said, ‘that was the end of the personal relationship between the two of them.’

The poignant fact of their bond is that when they divorced in 1996, they were married for 38 years. Of this, they had lived just four years together, with Nelson mostly away for political action, before he went underground and later got imprisoned for 27 years. During all of this, she lived her life as the matriarch of the movement, bearing the Mandela name and shaping the resistance. All in her own terms.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.