Last week, I attended a heritage walk in Old Delhi exploring the Thugs of India, organized by Gaurav Sharma from India Heritage Trails. After the walk, I picked up Mike Dash’s ‘Thug: The True Story Of India’s Murderous Cult’ and learnt quite a bit about this lesser known period of our history.

Bandits and highway robbers have always been a part of India’s folklore. The Vedas refer to Rudra as the ‘Lord of Thieves’. Valmiki was a reformed robber. The Vana Parva and the Shanti Parva of the Mahbharata makes references to the dasyus. The Buddhist tale Angulimala is about a robber who gets influenced by the Buddha. Huien Tsang, travelling in the seventh century, has written of his trysts with bandits and so has Ibn Batuta. In short, India was never a safe place for travellers.

Travelling in India, until the mid-19th century was an extremely dangerous pursuit. As travelling on a palanquin was exorbitantly expensive and the reserve of the ultra-rich, the vast majority of Indians, moved from one place to another by foot. And from simple economics, one can deduce the attractiveness of dacoity and robbery. What made the menace of thugs even more alarming in the early 19th century was the fragmentation of the Mughal empire and the subsequent collapse of the Maratha empire. Numerous soldiers and mercenaries who fought for these rulers, found themselves unemployed. Though the English East India Company replaced them, their writ didn’t cover large swathes of India. To add to this, terrible famines and failing agriculture, lured many to this ‘profession’. Once the thugs returned back to their villages, the local zamindars offered protection in return for a stake in the loot.

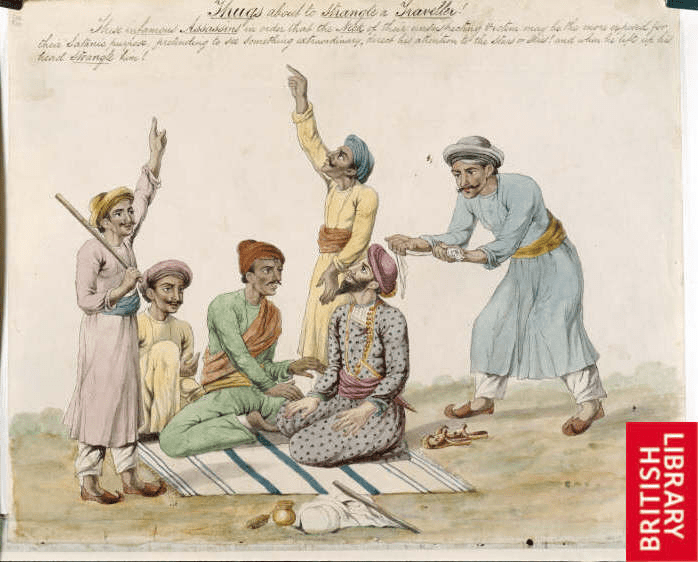

When the British began documenting the Thuggee – the secret network of thugs, slowly, information began to trickle in about the modus-operandi of the thugs. Thugs usually operated in bands and joined travelling groups. Once they won the confidence of their victims, they slaughtered them and made away with the loot. The murder was also methodical. Most strangled their victims with a noose. Roles and responsibilities were demarcated for each member. Professional gravediggers accompanying the thugs, slashed the stomachs (to prevent bloating which would raise buried bodies) and buried the victims in no time. As most travellers were hundreds of miles from their homes, their disappearance never raised any immediate enquiries allowing the thugs to easily get away. Policing in India was also rudimentary and conviction rates for arrested thugs were also abysmally low. One fascinating explanation for this was that the Hanafi school of jurisprudence in Mughal India awarded capital punishment only if the homicide involved a weapon usually associated with the shedding of blood. With a noose, no blood was shed!

The downfall of the Thugs began with the arrival of one English officer in the sleepy town of Jabalpur in the 1820s – William Henry Sleeman. Sleeman’s tenure in Central India also coincided with a sudden spike in travellers crisscrossing India with more than usual quantities of jewels and cash. One reason for this was the booming trade in opium. Since opium cultivation was fully under the control of the British, all illicit transactions had to be done through the hawala route.

Sleeman, with meticulous effort began the process of documenting every man named in every deposition made by every approver. Each Thug was assigned his own unique number. Detailed family trees, travelling routes, accomplice listings and time stamps helped spin a web around the thugs.

It was also during this period that the Thugs’ affiliation with the cult of Kali emerged. From whatever little I read, I wasn’t too convinced that the thugs shed all this blood solely to satisfy the cult of the Devi. A lot of this messaging was coloured by the prejudices and misinterpretations of the times. No serious anthropological study was done.Within a decade of Sleeman coming into the picture, the Thugee system was decimated. But so powerful was their hold on popular imagination, that even today, the Thugs are caricatured to no end.

The 2018 Amir Khan movie ‘Thugs of Hindostan’ had just one accurate scene in the beginning in which a group of travellers was accosted by a group of thugs. Everything else in the movie had just a ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ vibe and was all fantasy stuff.

In 1988, an Ivory-Merchant production starring Pierce Brosnan dealt with the Thugs. ‘The Deceivers’ was just ok. For me, getting to hear Nina Gupta, the wife of a Dalit weaver, speaking in Queens English was a tad too much.

And the final movie which I chanced upon was the best of the lot – though not explicitly based on the Thugee movement. Saif Ali Khan’s ‘Laal Kaptaan’ was spellbinding. A warrior-ascetic wandering in the Chambal ravines, in pursuit of a local lord and set in the fragmenting political landscape of the late 18th century was a revelation. It’s a pity that the movie is not well known.

In literature, Philip Meadows Taylor’s ‘Confessions of a Thug’ published in 1839 was the seminal work that catapulted the thugs into popular imagination. Even Queen Victoria was a fan of his work. In fact, until Kipling’s ‘Kim’ came out, this was the most popular work of fiction set in India.

By the 1870s the Thugs were more or less extinct in India. But the history of Thuggee led to the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871 which just labelled whole tribes as criminals. The Department of the Suppression of Thuggee and Dacoity remained in existence until 1904, when it was replaced by the Central Criminal Intelligence Department (CID).

PS: Sleeman was also responsible for the first discovery of dinosaur fossils in India! (Had recently written on some Dino facts)

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “The Thugs of Hindustan”