In the late 17th century, with scientific discoveries being the flavour of the season, Spinoza had already propounded his idea of God. Into this vibrant mix of new scientific thinking and philosophical daring entered Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

If there’s one person who can be defined as a polymath in the truest sense, it is Leibniz. His contributions spanned the fields of logic, philosophy, geology, history, engineering, law, linguistics and of course mathematics. (He co-invented calculus independently though Newton managed to claim the credit for the same).

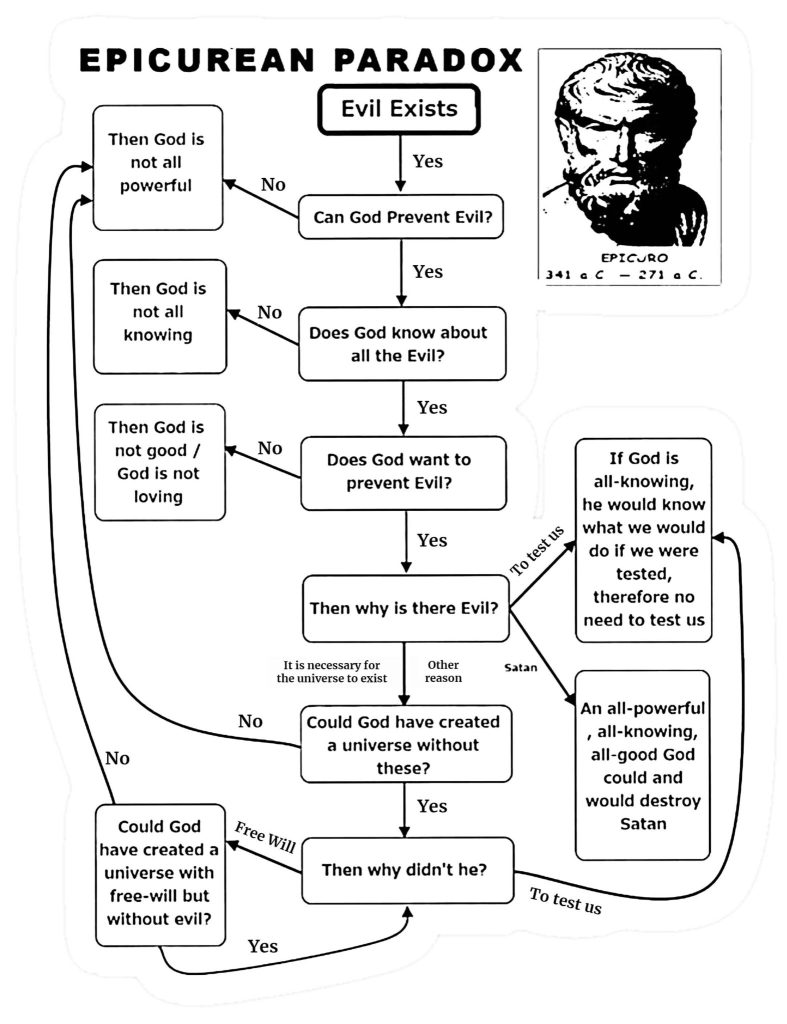

Leibniz was worried about cold rationalism upending cultural and spiritual traditions that grounded life. His entire philosophy aimed to create a system that would harmoniously marry the ancient, time-tested practices of spirituality with the emerging unrecognizable world that was becoming demystified by science. His most famous idea is that of ‘The Best of All Possible Worlds’. It was an argument against Spinoza and the Epicurean Paradox. (The paradox explained in the diagram below makes a compelling argument for a world without God).

For Leibniz, God was not this impersonal, cold, aloof personality of Spinoza. He was benevolent and cared for the well-being of the world. The world that he created was done in a measured, planned and thoughtful manner. It was thus the ‘Best of all possible worlds’. If God created it, it had to be the best. He circumvented the problem of evil by arguing that evil existed to bring forth the idea of goodness. Try telling that to the sufferer! Fundamental to this view was his Principle of Sufficient Reason which asserted that everything must have a reason, cause, or explanation for why it is the way it is and not otherwise. In simple terms, it means that there’s a reason or explanation for everything, whether it’s a physical event, a choice, or an existence itself. So if evil existed, well there was sufficient reason for it. If this world of God existed, then there had to be a cool enough reason for it. And trust God to have thought it through.

Voltaire, probably the smartest and sharpest chap of the 18th century, found this entire argument bogus. And to destroy it, he ended up writing the world’s most famous satire – Candide. Dr. Pangloss, the eternal optimist who believed that everything happened for a reason, even if the evidence around him was hard to reconcile with, was a caricature of Leibniz. At the end of the story, which is a series of ordeals that Candide and Pangloss undergo, when Pangloss recounts all their experiences and argues that everything that happened so far was for a purpose, Candide, calmly responds: ‘That is well put but we must cultivate our garden’. For Voltaire, abstract philosophy should never be a veil to hide behind. It’s within us to alleviate suffering and improve the lives of the people around us. The ‘garden to tend to’ becomes a metaphor and a call to action to shape a better world! To hell with Leibnizian optimism.

Another interpretation worth checking out:

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great Video Manish. A time to time reminder to withdraw and oause.

LikeLike