The most dramatic moment in the history of philosophy must be Socrates being forced to drink hemlock. If one is asked to pick another moment that could rank high on drama, my submission would be Spinoza’s excommunication in 1656 by the Jewish community of Amsterdam.

Spinoza’s parents landed up in the Netherlands after fleeing Spain thanks to the persecution of Jews by the Church and King. The Dutch Golden Age was underway and Jewish merchants could find the going not too bad in the Netherlands. Spinoza grew up in this world – a world of commerce and religious bloodlust.

While he began his education as a darling of his teachers, the tide slowly shifted. What began as innocent questions, slowly irked the Jewish clergy. How, he asked, could Moses have written all the first five books of the Torah if it also included incidents that happened after his death? How can the Jews alone claim to be the Chosen People by God. Does God not exist for the other communities? Was it just ignorance of the natural world that led people to these superstitious beliefs?

In no time, Spinoza was excommunicated from his religion (after also surviving an assassination attempt). No Jew—including even his closest relatives—was to have any further contact with him whatsoever. It was forbidden to speak with him, to communicate in writing with him, to read any texts he had written or might write in the future. It was even forbidden to remain under the same roof that sheltered him or to approach within four cubits—about six to eight feet—of his presence. Spinoza moves to the Hague and becomes a lens maker. The vocation suited him as it was solitary, intense, focused and above all, gave him adequate time to think and write. He dies at the age of 44 in 1677 with lung disease that is believed to have been caused by his job.

Descartes, who died a few decades earlier had already sent shockwaves through the religious and intellectual world with his arguments about the mind-body dualism. In Descartes’ framework, humans existed as a combination of two distinct substances, with only the mind being associated with the divine. This separation implied that physical reality could operate independently, governed by mechanical laws rather than divine intervention. By establishing the body as an autonomous “machine,” Descartes opened the door to a worldview where God was increasingly peripheral in explaining the natural world. Descartes’ theory thus planted the seeds of a mechanistic, secular worldview in which the material world could be understood, predicted, and controlled without direct reference to God—an idea that would later profoundly influence Enlightenment thinking. In some ways, his ideas reframed God as more of a clockmaker than an ever-present, unifying force. Spinoza saw this as a dangerous limitation, which is why he went on to propose a unified, immanent God within nature, leaving no room for dualism.

In Devra Lehmann’s easy-to-read biography Spinoza: The Outcast Thinker, the theory is summed up succinctly:

Spinoza often used the term “substance” to refer to the nature that he identified with God. According to Spinoza, everything that exists in the universe is either a substance or a mode. A substance needs nothing else to exist, but a mode exists only in connection to a substance…..But Spinoza goes much further than this. According to Spinoza, there is only one substance in the entire universe. Puppies, trees, rocks, and people, along with anything else that exists in the universe, are themselves modes of that single, all-embracing substance. This idea is really quite staggering. The glasses resting on one’s nose, the trees shading a window, the car parked on the street, the young woman walking by on the sidewalk, the sun shining in the sky above—all of it is really just a mutation of that one basic substance into some of its various modes. That substance just happens to be glasseslike on one’s nose, carlike in the street, and sunlike in the sky. Everything that exists, has ever existed, or will ever exist is part of that substance, and there is absolutely nothing beyond it. It is this infinite, single substance that Spinoza means when he speaks of nature, and this is the nature that Spinoza says is identical to God.

The corollary of this view of God was a rejection of the notion of revealed religion. In Spinoza’s world, there was no space for prophets, angels and superstitions. These were all human creations that emerged from man’s deep-rooted fear of the unknown. God was no wise, white-bearded, benevolent, omniscient being. He (or she) had no interest in your day-to-day lives. Little wonder that many considered him to be an atheist. For Spinoza, God was an intellectual project that could only be understood through reason. For him, this line of thinking, shouldn’t lead one to despair. Alternatively, it’s a call for action to live a moral life using the power of reason alone. One can argue that Spinoza was one of the earliest mavericks who started hammering away at the religious world that eventually led to the separation of Church and State, and the emergence of the modern State as we know it.

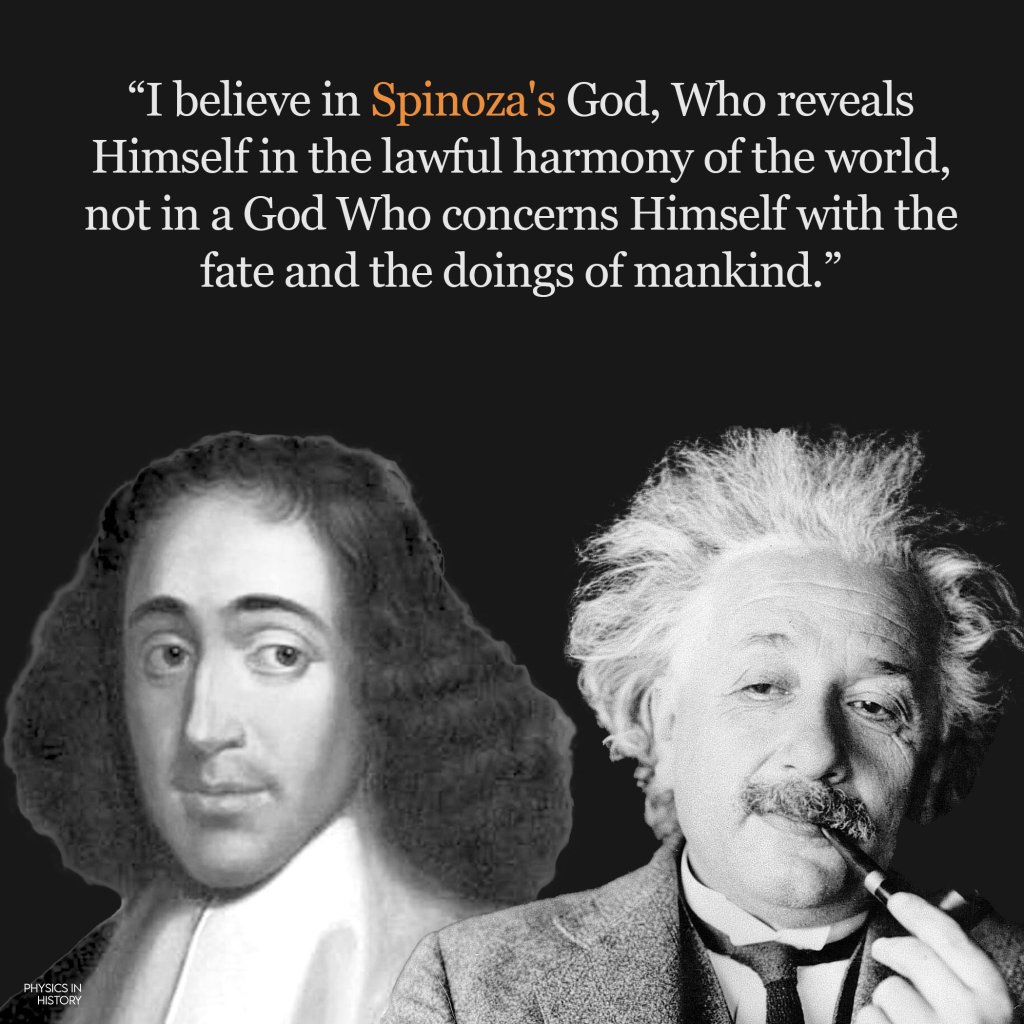

Three hundred years after his death, when Einstein was asked if he believed in God, he gave his response which is now probably the most famous quote of all time: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns Himself with fates and actions of human beings.”

For more information on Spinoza, the School of Life has a nice introduction to his philosophy :

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

lovely introduction to Spinoza

LikeLike