In the early years of my career in development, one of the raging debates was about the glory and ethical principle of working in the ‘field’ against joining organizations that paid lip service to development. Looking back, all of it appears so juvenile; as if development was only about working in rural, remote settings and sacrificing comforts for a larger ‘principle’. Can one truly empathize with the downtrodden? Where do we draw the line between empathy and preserving one’s sanity, between suffering and pursuing one’s desires? And does one become an interloper if the commitment vanes and falters? Isn’t all of this just an ego trip?

Simone Weil grappled with these questions and her life was proof of the complexity and absurdity of embarking on a life guided by such principles. In 1914, at the age of five, on coming to know about the hardships faced by the French during the Great War, she gave up sugar. (My eleven-year-old may disown me if I broach such an idea).

Weil’s philosophy was grounded on her theory of ‘Attention’. For Weil, attention means fully concentrating on the world, allowing for true empathy and the pursuit of justice. She argued that “we can never fully understand a fellow human being by staring, thinking, or even commiserating with her. Instead, understanding comes only when we let go of our self and allow the other to grab our full attention. In order for the reality of the other’s self to fully invest us, we must first divest ourselves of our own selves.” This was the standard against which she measured her life.

Despite being a college topper and secure in a teaching gig, Weil decides to pursue her radical philosophy of attention and empathy. She resigns and works in a factory to understand what the meaning of alienation of labour actually meant. Her experiences convince her that even Marxists were missing the point as no theorizing could match up to the lived experience of the factory. Weil follows this up with a stint in a mine.

When the Spanish Civil War breaks out, Weil signs up with the conviction that only fighting and putting one’s life on the line was the truest resistance to Fascism. Never mind that she was hopeless and physically unfit for the job; in fact she accidentally steps on a boiling cauldron of water which immobilizes her and ends her dreams of fighting. Her regiment, in a few weeks after this, gets massacred. For Weil, resistance is a reflexive trait in all living beings. We flinch when we are poked. But when reflection is brought to resistance, it attains a radically different flavour.

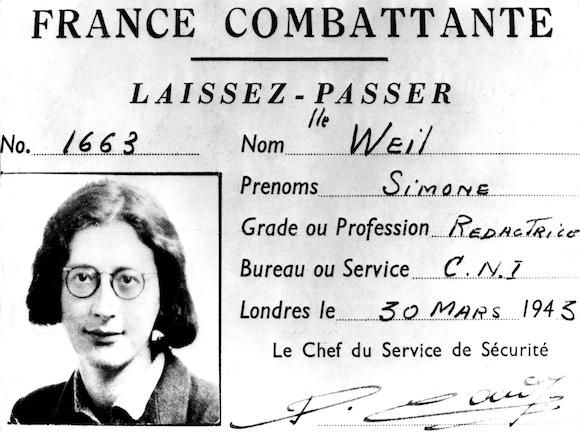

During the Second World War, due to her Jewish background, she flees France and ends up in the UK where she volunteers to fight with de Gaulle’s Resistance movement. When she asks to be parachuted into France along with a nursing contingent, de Gaulle famously sums her up as “mais, elle est folle’ (But, she is mad!). In 1943, at the age of 34, she dies in England out of chronic malnutrition and tuberculosis. If there’s one person, who died by her philosophy, it must be Weil. She literally starved herself to death in solidarity with the oppressed.

For Albert Camus, Weil was ‘the only great spirit of our time’. In 1957, when he leaves for Stockholm to collect his Nobel, it was at Weil’s house that he stops by to spend a few meditative moments. The other existentialist superhero de Beauvoir also had an encounter with Weil which I read in Robert Zaretsky’s The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas –

Simone de Beauvoir recalled her first and, it turned out, last conversation with Weil. Hearing the stories circulating about Weil—most famously, when she burst into tears upon learning of a famine ravaging China—Beauvoir was eager to meet her fellow philosophy student. When she finally did, the meeting did not last long. After brief introductions, Beauvoir must have touched on the Chinese famine, because Weil peremptorily announced that “one thing alone mattered in the world today: The Revolution that would feed all the people on the earth.” When Beauvoir demurred, suggesting that the point to life was to find, not happiness, but meaning, Weil cut her short: “It’s easy to see you’ve never gone hungry.”

The other contemporary of Weil who was also celebrated for his saintliness and masochism was our own Mohandas Gandhi. And Orwell’s Reflections on Gandhi is probably a good place for a critical evaluation of his own ‘saintliness’.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “On Simone Weil”