Each time I hug and pamper my children, I subconsciously know that I’m contributing to the scaffolding of their mental architecture and shaping the landscape of their emotional world. And that dear reader, is the influence of Freud in our lives. Though his ideas are widely discredited today, Freud’s enduring contribution lay in being the first person who put sex on the map of human psychology. As a scholar put it: “Freud is like the weather. He is everywhere’. Freud single-handedly, through a lifetime of writing and practice, created the field of psychoanalysis from scratch and changed forever the meanings associated with dreams, desires, and repression and lit up the erotic space that the family is.

The debt therapists, counselors, and coaches owe to Freud is immeasurable. Much of the therapy-speak in vogue today stems from his pioneering discovery of talking therapy aka psychoanalysis. (A related piece on India’s most famous psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar is here)

Peter Gay’s ‘Freud: A Life for Our Time’ and British psychoanalyst Adam Philips’ ‘Becoming Freud’ were excellent biographies that gave me a measure of the man. Freud invented psychoanalysis ‘mostly out of conversations with men but through the treatment mostly of women’. Freud’s own family and childhood was a laboratory of sorts that triggered a lot of his ideas.

Freud’s father married his mother, when he was forty, twenty years older than his bride. Two sons from his first marriage—Emanuel, the elder, married and with children of his own, and Philipp, a bachelor—lived nearby. And Emanuel was older than the young, attractive stepmother whom his father had imported from Vienna, while Philipp was just a year younger. It was no less intriguing for Sigismund Freud that one of Emanuel’s sons, his first playmate, should be a year older than he, the little uncle.

His mind was made up of these things—his young mother pregnant with a rival, his half-brother in some mysterious way his mother’s companion, his nephew older than himself, his best friend also his greatest enemy, his benign father old enough to be his grandfather. He would weave the fabric of his psychoanalytic theories from such intimate experiences. When he needed them, they came back to him.

With such childhood memories and influences, it’s not hard to fathom the sources of his ideas. Freud was surrounded by strong women and the erotic charge that they probably had on him can’t be underestimated.

From his earliest days onward—to begin with the fantasies—Freud had been surrounded by women. His beautiful, dominant young mother shaped him more than he knew. His Catholic nurse had a somewhat mysterious share, abruptly terminated but indelible, in his infantile emotional life. His niece Pauline, about his own age, had been the first target of his youthful erotic aggressiveness. His five younger sisters arrived in rapid succession—the youngest, also a Pauline, was born when he was not yet eight—invading the exclusive attention he had enjoyed as an only child, and presenting themselves as inconvenient competitors no less than as rapt audiences. The one great love of his adult life, the passion for Martha Bernays that flooded him in his mid-twenties, struck him with unmitigated ferocity; it brought out a fierce possessiveness and subjected him to bouts of irrational jealousy.

Freud’s groundbreaking works, such as ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’, ‘Civilization and Its Discontents’, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’, ‘The Ego and the Id’, and others revolutionized our understanding of the unconscious mind and human sexuality. While the Nobel Prize for Medicine would have been a stretch considering the complexity and genre-defying nature of psychoanalysis, the Literature Nobel would have elevated its own reputation had he been considered. Freud, thus joined the ranks of a long list of modern-day literary giants who were never invited to Stockholm – Proust, Joyce, Kafka, Woolf, Nabokov, Tolstoy, Borges… Psychoanalysis, in the early 20th century was portrayed as a ‘Jewish science’ as most of Freud’s followers were Jews. Wonder if that too played against him. In popular media, Freud was this aged, bearded, stiff, cigar-smoking German-speaking radical who was destroying all notions of respectability by talking about Oedipal complexes, repressed desires, and sexuality.

The last decade and a half of his life was miserable. His cigar addiction gave him oral cancer at the age of 67. Until his death sixteen years later, he endured close to forty surgeries, and radiation therapies and wore a painful prosthetic. Despite all this, he soldiered on and kept consulting. To top up this misery, a monster came to power in Germany and set his sights on the Jews. Freud’s works were part of the Nazi Book Burnings. The writing was now on the wall for the czar of psychology. The eighty-two-year-old had to leave and in 1938, moved to England, where he died a year later just as WWII broke out. Zweig, on whom I had written earlier, writes about this phase in his superb memoir. These last years were also captured in a graphic novel which was underwhelming for me – ‘Through Clouds of Smoke: Freud’s Final Days’

Modern people, it seemed to Freud, were the only animals that were ambivalent about their own development; they longed to grow up and they hated growing up, and sabotaged it. In other words, we can see Freud now, consciously or unconsciously, wanting to pick up the threads of an abandoned Romanticism, and reworking them in a scientific, predominantly Darwinian context. The child, the dream, development as the narrowing of the mind and the stifling of the heart; society as the enemy of the individual’s passion and vision; the suspicion of traditional forms of authority; a new exhilaration about the possibilities of language

What a genius!

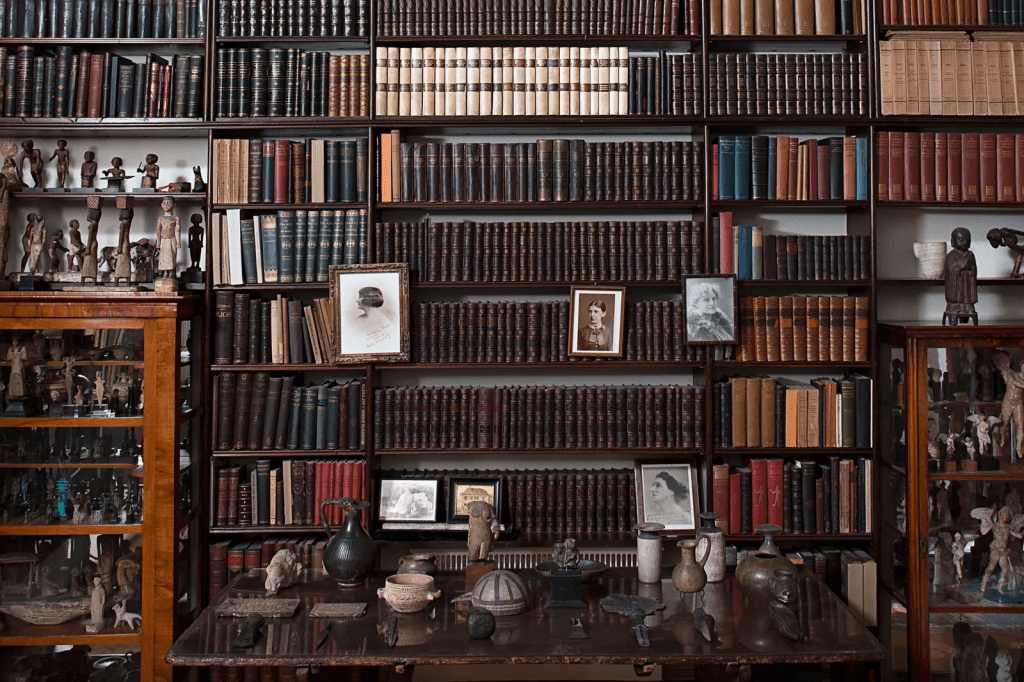

Freud was also a maniacal collector of antiquities. He amassed a private museum of more than ‘two thousand Greco-Roman statues, busts, Etruscan vases, rings, precious stones, Neolithic tools, Sumerian seals, Egyptian mummy bandages, Chinese jade lions, and Pompeiian penis amulets’. For Freud, there was no better metaphor than archaeology to describe the excavation that he himself was undertaking of the human mind.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “On Freud”