The 1930s was a remarkable decade for Indian writing in English. Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable and R.K. Narayan’s Swamy and Friends were published in 1935 and Raja Rao’s Kanthapura followed in 1938 – a year before WWII.

Last month, I picked up Raja Rao for the first time and tackled Kanthapura, The Cat and Shakespeare and his collection of essays titled ‘The Meaning of India’. Raja Rao was a Kannadiga, who grew up in Hyderabad, studied in Alligarh, went to France and kept visiting Trivandrum on and off. His deep grounding in the Indian philosophical traditions seeps into his books and his use of the colloquial tempo while writing in English was novel.

We liked Roosevelt because we hated Churchill. We love what we cannot have. When we have it, we have it not, because what it is not, is what we want, and thus on to the wall. The mother cat alone knows. It takes you by the skin of your neck, and takes you to the loft. It alone loves. Sir, do you know love? O Lord, I want to love. I want to love all mankind.

In the Meaning of India, there’s an arresting account of Rao’s meeting with Nehru in 1935. Nehru visits Europe to be with his wife who was dying from tuberculosis. Rao seeks him out and manages to get an appointment to meet the Indian ‘Boddhisatva’. Nehru asks for three bottles of Evian from Rao.

‘You certainly believe in something, Panditji? In some form of Deity, in philosophy?’ ‘Deity, what Deity?’ He twitched angrily. ‘Why Siva and Parvati, Sri Krishna!’ ‘Three thousand years of that and where’s that got us—slavery, poverty.’ ‘And incomparable splendour, even today.’ ‘What, with twenty-two-and-a-half years of life expectancy and five pice per person per day of national income? We’ve had enough of Rama and Krishna. Not that I do not admire these great figures of our traditions, but there’s work to be done. And not to clasp hands before idols while misery and slavery beleaguer us.’ ‘Yes, and after that?’

So typical of Nehru. Restless and impatient with ‘traditions’ and fixated on the tasks at hand.

Later, Nehru writes back to Rao seeking his help to fix an appointment with Andre Malraux – the most famous Parisian of the time. During this meeting, Nehru steps into Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Company and gets himself a copy of Ulysses.

He held it shyly in his hands, and looking mischievously at me, he remarked: ‘You know, in India, it’s a proscribed book.’ And he smiled back to me as if in an act of connivance. He could play.

Malraux later returns to India as de Gaulle’s ambassador and once again Raja Rao accompanies him in his first official meeting with Nehru in New Delhi. Delhi’s diplomatic enclave Chanakyapuri has a lane named after Andre Malraux which co-incidentally was adjacent to the first office I worked in.

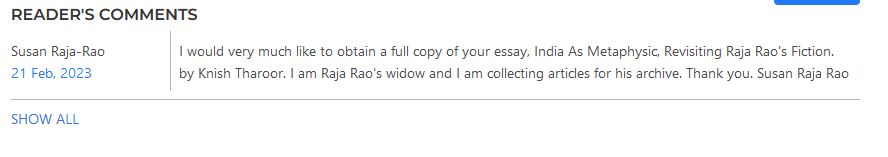

Kanishk Tharoor has a piece on Raja Rao’s fiction which unfortunately is pay-walled. However, what caught my attention was this comment below the piece:

So poignant!

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Raja Rao”