Despite completing four decades on earth, I’m yet to learn a single mantra or a complete prayer. While I’m fascinated with rituals each time I see them, I’ve never felt the need to bow down to them or worry about not giving them adequate ‘respect’. I’m convinced that the hold that religion has over our lives is solely driven by our fear of death and worse, the fear of losing our loved ones to disease or an untimely death. Remove these scenarios and the supernatural suddenly becomes mundane.

While a world where everyone thought like me would improve human flourishing, such a world would also be lacking an essential ingredient of what makes us truly human – our need to find meaning for our lives. The need for ceremony is deep-seated and is manifested in the diverse ways we celebrate the most important moments of our personal and public lives.

During the hunter-gatherer stage, the elements were what decided our fates. The sheer fear and inability to master them were the earliest drivers for the birth of rituals, priests and proto-religions. The dominance of Indra, Agni and Vayu in the Vedas compared to the later emergence of a cowherd-God like Krishna is a reflection of this reality. The discovery of burial sites from 9000 BC like Göbekli Tepe have also convinced some anthropologists that it was the pull of rituals and ceremonies that drew people to central locations eventually leading to settled agriculture (instead of the commonly held belief of it being the other way around). As each culture expanded, the driving force for subsuming other cultures was the sophistication of the rituals of the victorious ones. Even today, the defining feature of a ritual is its adherence to a particular script and the requirement to not deviate from the ‘steps’. Break this rule and the whole spectacle suddenly goes poof.

Since 9000 BC, we’ve travelled a lot. But even today, rituals are all around us. The need to Instagram our ceremonies can only partially explain the popularity of some of the kitschy rituals like Karwa Chauth, bachelorette parties, baby showers etc. The actual reason in my opinion is that rituals such as rites of passage are a reminder of our own mortality. Few cultures have developed a vocabulary that overtly accepts this aspect of the human condition. A naming ceremony initiates a baby into childhood, a convocation marks a person as a scholar, a marriage ceremony gives social sanction to living together, a funeral allows us to grieve and mark the deceased as an ancestor. The first COVID lockdown was marked by all of us creating rituals to make sense of the bewildering realization that the ground beneath our feet was slipping away.

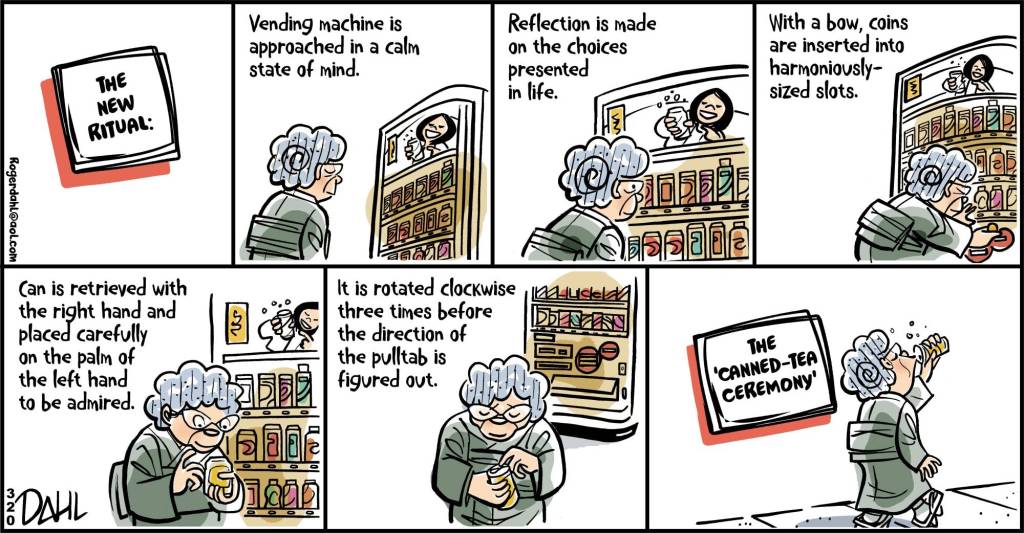

Rituals can also become a proxy for exclusion. When you think of it, the codes of fine dining, the steps of a Japanese tea ceremony, the protocols of diplomacy, the drills of army regiments, the banter of a kitty party are nothing but socially sanctioned rituals that bestow membership and mark the practitioners as representatives of a specific ‘class’. Be ignorant of them, and you’ll probably end up like me – aloof, rootless and a member of no group. Is philistine the word for it?

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “On Rituals”