Why is owning a house such an emotional pull for humans? Why do we derive so much joy from the act (in some cases the mere thought) of designing our living spaces, decorating rooms and pondering about the changes that would be necessary to be initiated in as we age. While a lot of it can be ascribed to status-signaling, the sheer amount of investment that a house warrants is tremendous.

Personally, I’ve never had the fascination of owning a house. While the steep price is one reason that has kept my desires at bay, the whole emotionally-draining feat of choosing, investing and worse of all – maintaining it is just not for me.

Leaving this issue aside, the pertinent question to ask is: Are buildings eternal? What makes it hard for buildings to survive across generations? Is there merit in our own government’s argument that the North and South Blocks of New Delhi have outgrown their utility as seats of power? Why do certain cities have a penchant for tearing down buildings every now and then (think Dubai).

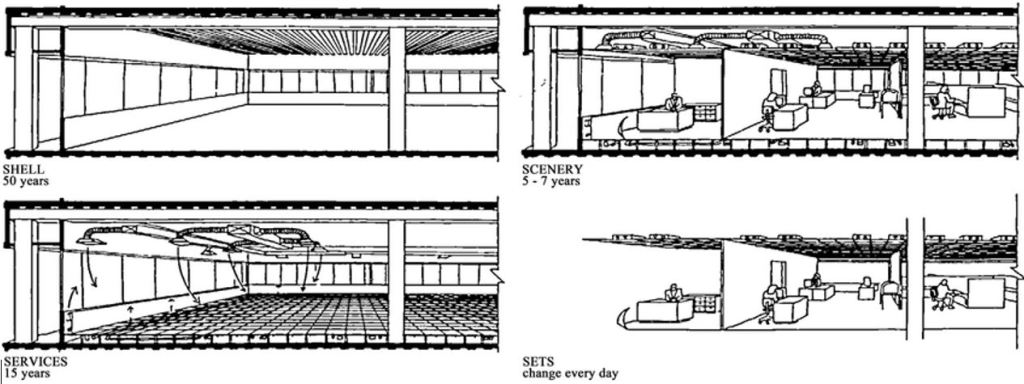

The architect Frank Duffy succinctly expressed his take: “Our basic argument is that there isn’t any such thing as a building. A building properly conceived is several layers of longevity of built components”. His framework to understand how buildings evolve can be a handy reckoner. For Duffy, every building can be broken down into the components of:

- Shell (Structure)

- Scenery (Internal Layout)

- Services (Wiring, Plumbing etc)

- Sets (Furniture, consumer goods)

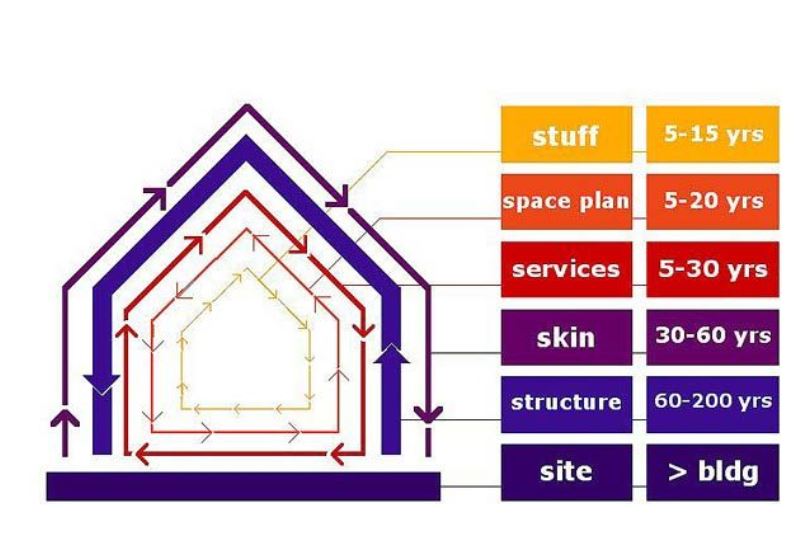

Stewart Brand, in How Buildings Learn, further elaborated this idea and postulated that all buildings have a:

- Site

- Structure

- Skin

- Services

- Space Plan

- Stuff

The layering also defines how a building relates to people. The building interacts with individuals at the level of Stuff; with the tenant organization (or family) at the Space plan level; with the landlord via the Services (and slower levels) which must be maintained; with the public via the Skin and entry; and with the whole community through city or county decisions about the footprint and volume of the Structure and restrictions on the Site.

Slow constrains quick; slow controls quick. The same goes with buildings: the lethargic slow parts are in charge, not the dazzling rapid ones. Site dominates the Structure, which dominates the Skin, which dominates the Services, which dominate the Space plan, which dominates the Stuff. How a room is heated depends on how it relates to the heating and cooling Services, which depend on the energy efficiency of the Skin, which depends on the constraints of the Structure. You could add a seventh “S”—human Souls at the very end of the hierarchy, servants to our Stuff.

For Brand, all buildings are in a constant change of flux. Like living organisms, they breathe, age, shrivel or at times transform into new entities. This interaction between the built environment and the humans who inhabit them is often an unnoticed aspect of modern civilization. Driving this are real estate prices, heritage laws, and the impact of the ‘vernacular’ on the structure and form of buildings in the form of building codes.

Hence, designing buildings that are practical and can withstand the test of time is of paramount importance. The very fact that our buildings are rectangular is driven by the possibility of the shape-facilitating expansion (both vertically and horizontally) offered by rectangles. Ever wondered why your house doesn’t have round/curved walls?

Tribal cultures the world over have beautiful round dwellings, but the shape of civilization is rectangular

Often the necessity to be practical gets lost when architects aspire to become artists instead of craftsmen. The anthropologist Henry Glassies’ distinction can be instructive: If a pleasure-giving function predominates, the artifact is called art; if a practical function predominates, it is called craft.

To cut a long story short, if you don’t have a house of your own, chill. In a few decades, it’ll transform; in most cases decay.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.