Last month, I spent the Independence Day weekend with my family exploring Ahmedabad and Baroda. The highlight of Baroda was the audio-guided tour of the Lakshmi Vilas Palace. We spent close to two hours admiring the palace and its treasures. Like any major Indian palace tour, there were manicured lawns, dazzling chandeliers, the mandatory tiger skins, rusted weapons, letters from the high and mighty, cutlery and most impressive of all – some exquisite Raja Ravi Varma originals. But what I thought to be a comprehensive tour, in hindsight, turned out to have omitted one very important facet of the King who constructed the palace. Sayajirao Gaekwad shaped the careers of two of, arguably, the greatest Indians ever. One was the architect of the Indian constitution, B.R. Ambedkar. The second was the person whose name is synonymous with Pondicherry today – Aurobindo Ghosh.

Aurobindo was raised by his father as an Anglophile with the intent to one day crack the Indian Civil Services examination. But just like ascetic Rishyashringa’s intoxication on seeing the apsaras, our Aurobindo gets all worked up on discovering India’s culture and history; rebels against his father by famously refusing to attend the equestrian test which was mandatory for the civil services examination then and becomes an out-and-out nationalist.

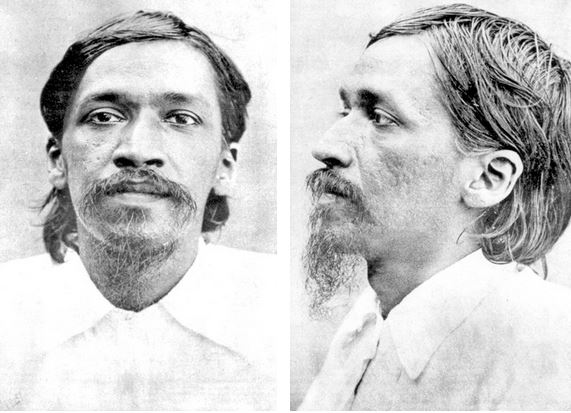

It was in this backdrop that Sayajirao Gaekwad gave him his first break and hired him to join the Baroda Civil Services. Soon, Aurobindo ends up in Bengal – the hotbed of the Indian Nationalist movement then. He gets involved with the Anushilan Samitis – a quasi-militant body, becomes the first principal of the National College (which evolved into today’s Jadavpur University) and later edits Bande Mataram for which he lands up in the radar of British Intelligence. The Alipore Bomb case has him arrested as a prime suspect but after a year of detention, Aurobindo is set free by the British – emerging as one of the most prominent leaders of India then. (The next big name of the time was Tilak who was locked up in distant Mandalay).

In ordinary cases, Aurobindo would have been expected to continue this path of resistance. But fearing arrest by the British, he moves to Chandernagore, a French territory in Bengal and finally in 1909 goes to French Pondicherry by a steamer to never set foot in British India ever again. From this point on, Aurobindo is no longer the firebrand extremist. Spirituality becomes his calling and the raison-de-etre of his life.

Joining Aurobindo in Pondicherry was Mirra Alfassa, who later becomes ‘The Mother’ or ‘La Mere’ (I wonder if there’s a guru anywhere in the world whose name matches the one listed in their birth certificate). Under her vision, the Ashram grows into an internationally recognized institution, attracts followers from different countries and the idea of a dedicated commune in the outskirts of Pondicherry was conceptualized and christened as Auroville.

To better understand this phenomenon, I picked up two recent works that document this period – Akash Kapur’s ‘Better To Have Gone: Love, Death and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville’ and Jesicca Namakkals’ ‘Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India’ . Both these books tear apart the concept of Auroville being this rosy experiment where people from different cultures intermingled and strove towards self-actualization. What we get to see is the usual power politics involved in every institution-building initiative and the high price borne by the powerless.

Kapur, who was raised in Auroville and who is married to a woman whose parents died under mysterious circumstances in the commune, uses the backdrop of this family saga to paint a sordid picture of Auroville. The Ashram and the growing commune encouraged an atmosphere of blind belief in the Mother’s spiritual powers, propagated rampant pseudo-scientific beliefs around medicine, turned a blind eye to free sex (the only thing that would ever convince me to join a commune) and created a band of disillusioned hippies (is this an oxymoron?).

Namakkal’s analysis, on the other hand, was more of an academic examination of how the Ashram and Auroville emerged as a rosy metaphor for France’s ‘benovelent’ rule over India.

Interpretations of the decolonization of French India as peaceful and friendly serve to distance people from the histories of the horrors of Partition or the brutal violence France enacted upon colonized populations in North Africa, Indochina, and Madagascar during the high period of anticolonial movements and decolonization between 1945 and 1962. Puducherry, the minor French possession on the Coromandel Coast, has become in this way a sort of crossroads of modernity/coloniality, a series of paths that cross the French Indian past; the Indian present; and the evolutionist, utopic future projected by the intentional community of Auroville.

According to historians Nicolas Bancel and Pascal Blanchard, “Memory is not history,” as memory is based not on archival sources but instead on the cumulative socialization that interprets history through shared experiences and memories. The colonial memory of French India becomes intertwined with the Ashram and Auroville, because the Ashram and Auroville exist in the present moment in a way that French India does not. The way that the colonial past is remembered may or may not be based on historical evidence, often leading to colonial nostalgia, which, Bancel and Blanchard argue, often legitimizes colonial projects as successful in retrospect—a sentiment that swirls around discussions of French India in popular media and culture (in France, India, and the United States).This book takes the colonial memory of France as a “good” colonizer and turns it on its head in an effort to deepen historical and popular understanding of the limits, struggles, and failures of decolonization to do away with colonialism in ways significant to people on the ground.

The whole Auroville experiment, according to Namakkal is nothing but ‘anticolonial colonialism’

In and near Pondicherry, the Aurobindo Ashram and Auroville serve as examples of how liberal discourse rooted in multiculturalism, spirituality, equality, and utopianism has displaced local Tamil populations from land and history, time and space. While the Ashram occupies a major part of the ville blanche in the Union Territory of Pondicherry, Auroville is technically outside of Pondicherry, on land that was under British, not French, occupation. However, the extension of the Ashram beyond the colonial borders that previously separated the territories has extended the French influence onto neighboring Tamil land—one important difference being that the people who have been displaced by Auroville were never given a chance at French citizenship.

Everyone who wanted to come to Auroville was required to submit an application, with a picture of the applicant, which would go directly to the Mother. The initial application had twenty-four questions, beginning with name and nationality and ending with “What can you donate to Auroville?” Potential Aurovilians were asked to explain why they wanted to come to Auroville and questioned as to whether they were familiar with the philosophies of the Mother and Aurobindo. The Mother and the other organizers knew that their goals appealed to a type of person they did not desire: those without any money, who showed up lost and poor. They wanted to make sure that the applicants they accepted were not simply drifters or people looking for welfare. M. P. Pandit, the secretary of the Sri Aurobindo Society who oversaw the application process, admitted, “We have a hard time keeping out the hippies. We do not want them, they are not serious about anything.”

I’ve never been to Pondicherry despite being married to a woman who was born there and who spent the first 23 years of her life in the city. I probably now have a different perspective to ‘see’ the city which may be a counter to the romanticized versions that I’ve encountered ad nauseam in so many films, songs and Facebook posts.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.