When I landed in Delhi 14 years ago, I was miserable. Affordable housing was a joke, eating out was costly, travelling home once in a few months was an expensive proposition and to make matters worse, I was surrounded by people who lived in an alternate universe. Economic worries never troubled them.

Fast forward to 2023. I’m better off today. I now earn sufficiently enough to no longer sweat about the small things. How I reached here was through a mix of luck, well-networked friends and dare I say, my own skills and choices. The fact that I lived in a city with sufficient opportunities, enterprises, and smart people all around also helped me. Are most of my peers doing better than me today? Definitely – if you use wealth as the yardstick. But if the metric for comparison is say, time and leisure – then I’m probably damn rich.

The reason to narrate this is not to blow my own trumpet but to contextualize the issue of Economic Inequality. Each time Oxfam brings out their Inequality reports, a lot of media attention is on the issue of skewed wealth-ownership and the proposition of how this can be magically solved with a wealth tax on the super-rich. To imagine millions struggling to scrape through their existence while a small sliver enjoys unlimited bounties is enraging and ethically wrong on many counts. But, as correlation is rarely causation, one needs to examine and probe the idea of Inequality a bit more.

As mentioned earlier, economic indicators often end up hiding a myriad of additional parameters such as the joy derived from leisure, the individual choices made by people on their choice of work, or even unpaid vocations such as caring for the old and infirm. One cannot (and should not) compare the value of a Gangubai Hangal with that of a Byju Raveendran, by merely comparing their bank balance.

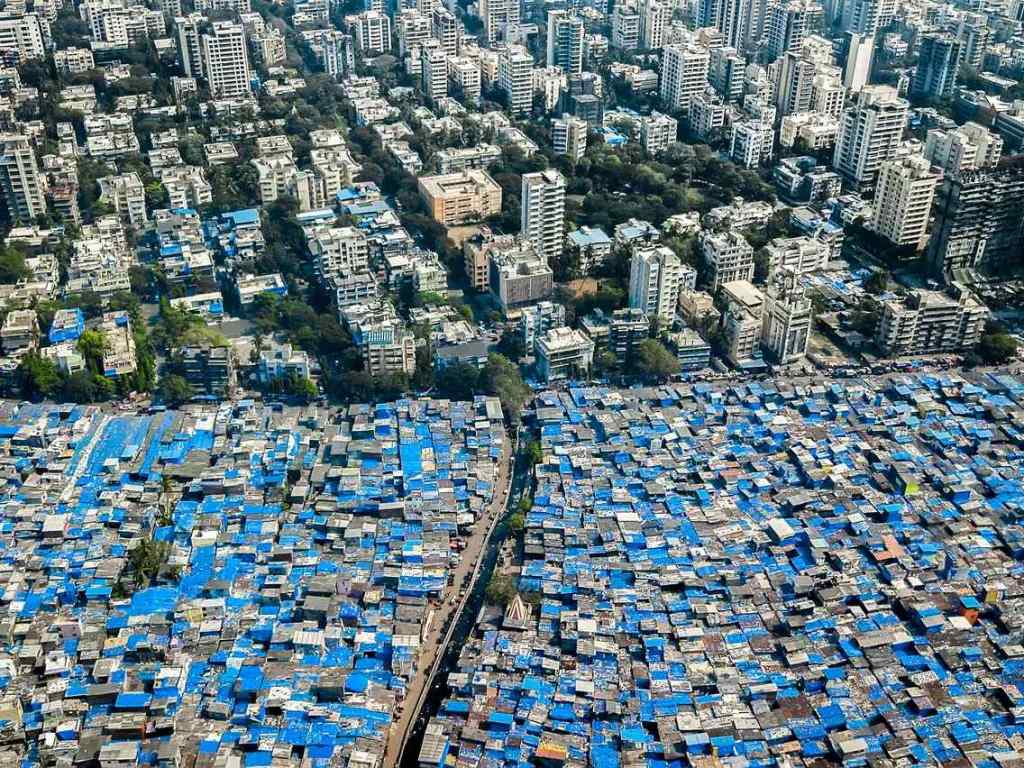

Inequality is a loaded term which sometimes implies that all differences are unethical, unjust and that all societies should aspire to be equal. The sheer impossibility of being able to fathom such a society shows how complex redistribution of incomes can be. Poverty and inequality are often used in the same breath. But it’s important to note that an unequal society can be prosperous (most Western democracies) while an equal society can be poor too (Lebanon, Syria, Afghanistan etc). Often, poverty is largely a result of poor government capacities and political foolhardiness. The state of our public education, the absence of the rule of law, our pathetic scientific research capabilities, militant trade unionism, the license-raj and populist policies are probably more responsible for keeping millions in our country poor than the presence of a few billionaires. I had written earlier how skewed housing policies choke affordable housing in many of our cities.

Disparities in income can act as a trigger and motivate people to work harder and create value in society. The mere existence of a large market spurs industries to mass produce items thus making them affordable. The Apple Vision Pro , launched earlier this year is unaffordable for me. But I’m willing to bet that in less than a decade, this will be a common sight in our cities. The same happened with air travel, personal computing, and smartphones. All scientific breakthroughs happen in unequal societies, primarily to cater to the rich. With time, they become universally available, spur innovation and make lives of the poor relatively better off. Remember, global poverty has been going down over the last century.

Rags-to-riches stories that we celebrate, be it of Prime Ministers, sports stars, movie celebrities or CEOs are a testimony to the pull that inequality can have on our thinking. Virat Kohli’s timing, Tiger Woods’ swing or a Federer’s forehand are rewarded by the markets due to the incalculable joy they provide to millions. How should the State intervene in these cases? Should they be celebrated and encouraged or should their wealth be seen as a ‘crime’ to be ‘redistributed’?

The markets reward us for the risks taken. When happy Bhutan decides to open up their borders to get on the free-markets bandwagon, you realize that Gross National Happiness can only take you so far. At the end, societies need wealth, wealth creators and a satisfied citizenry. For all of these, one needs risk takers, mavericks and aspirants who decide slogging to move away from the status quo is a worthwhile pursuit. Ask any migrant moving to a booming city about their most pressing concern. It’ll invariably be about safety, healthcare, education for their children and decent housing. It’ll never be about inequality.

So, in short, the next time someone begins lamenting about the increasing inequality, probe them on the reasons for mass poverty. The Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index influenced by Amartya Sen’s work on capabilities would be a good place to start. Let the rich become richer and let the governments do what government needs to do – ensure a just society by providing opportunities to all to thrive, without bothering about redistribution.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.