Human beings are self-centered. When I perform an act of altruism or a ‘good deed’, all that I’m doing is meeting my own self-interest – the need for acknowledgement from my peers, an addiction to the warm afterglow or in some cases a quest for glory. This is true for you, me and everyone else.

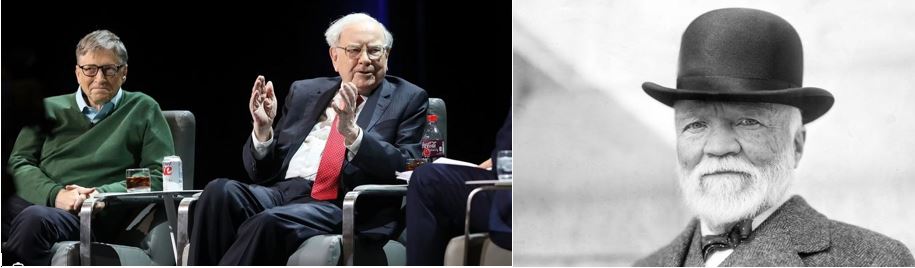

When I donate a coin, make a UPI payment or write a cheque (never done that yet), I’m showing my allegiance to the cause and hoping to reap the social capital that can be harvested through the act. The act here can range from becoming a paid subscriber to a news portal, to supporting an Instagram influencer, to donating to post disaster relief or to volunteering in a clean-up drive. When you and I do this, the impact of our deeds on the larger scheme of things is often negligible. But say, if you are a Bill Gates or a Warren Buffet, the action is no longer a mere ‘act’ but ‘philanthropy’. And hence, its important to understand the issue better.

While I work in development and am aware of the impact that donor resources can play in supplementing and complementing the State’s efforts, I’m also a student of International Relations who’s aware that all aid comes with a lot of historical baggage and political compulsions. During the hey days of colonialism, the justification for subjugation was often around the ‘White Man’s Burden’. But when the Post World War II world order suddenly made colonialism unfashionable, what we got was a string of nationalist movements culminating in independence and the colonial powers conveniently realising that the ‘burden’ was no longer theirs. Aid followed, in bits and pieces.

Philanthropy is a different animal. Here, the drivers are corporations, individuals, and their foundations. The thorniest issue around philanthropy is the question of whether a self-interested action can ever be truly philanthropic.

Academics like Lynsey Mc Goey (‘No Such Thing as a Free Gift’), paint a bleak picture of the role of philanthropists and sound a warning over their increasing influence in policy making. She starts from Andrew Carnegie’s legacy in expanding the network of public libraries all over the States despite having no qualms in breaking up labour disputes in the most brutal manner; details out Clinton’s shenanigans with the business magnates involved in Kazakhstan’s uranium contracts and their subsequent donations made to the Clinton Health Access Initiative and finally culminates with the poster boy of global philanthropy – Bill Gates. A lot of criticism around Gates has been around Microsoft’s controversial history around patents, monopoly practices and the ruthless way they ran their business. McGoey, rather unconvincingly, wonders aloud if the same mogul can now be entrusted with decisions around generic drugs, access to healthcare and agricultural policies.

For McGoey, Coca Cola is an evil corporation; Warren Buffet making money out of Coke is bad; him investing the money in the Gates Foundation is worse; and the Foundation then advocating on global health is the worst. While I can see the emotional resonance of such messaging, I’m too much of a realist to fall for the narrative. The world we live in today is complex and enmeshed with global corporates (For instance, India’s state run Life Insurance Corporation received approximately $400 million as dividends from the Indian Tobacco Company in the last financial year). State capacities in most of the Global South are weak, limited and over-burdened. From a distance, policy making can appear to be all about writing up a nice well-meaning document and implementing it. Few, apart from the practitioners, understand the complexities involved in each stage of policy making – from identifying the challenges, chalking out the strategies, listing the trade offs and deciding on the final step to finally ‘facing the music of the electorate’. While the ultimate responsibility for citizen well-being must wrest with the Government; aid and philanthropy, despite their baggage, do have a role in improving people’s lives.

Billionaires are not bad for society. You probably came across this post on WhatsApp (run by a billionaire), or on Twitter (run by another billionaire) and may be reading it on a phone probably purchased from Amazon (also owned by a billionaire). Equally important to note is that you’re probably feeling safe and secure in your home or office due to the presence of the State (which should never be run by billionaires). To put it simplistically, the heart of the arguments about philanthropists lies in this tension between separating the ever-increasing tentacles of private enterprise from the role of the State. Global capitalism and big businesses have created ecological havoc in a hitherto unparalleled scale. But equally important to note is the fact that human well-being (on almost every count) has improved since the Industrial Revolution.

The corollary to be asked is: What exactly should the role of the state be? Should the State do more or should the State focus only on the Right to Life, Liberty and Property and leave the rest to the Markets? What should be the parameters for the State’s role in social welfare? And more importantly, why is the same scrutiny of big business not applied to the other equally devastating phenomena of human life such as, say, organized religion?

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “On Philanthropy”