To describe the early 40s as a unique period in Indian history would be an understatement. World War II was raging, Britain was valiantly holding on against the Nazis, the Japanese were marauding in the seas of Southeast Asia, Chiang Kai-shek was battling them with US supplies airdropped from India, Burma had fallen and it was just a matter of time for India to capitulate and follow the same fate. It was in this backdrop that the Quit India Movement was launched by the Congress in 1942 and understandably met with the full might of the British Government – the Congress was banned and the entire leadership of the Congress jailed.

The political vacuum that emerged from this was fertile ground for the Muslim League to hard-sell their idea of Pakistan. But the irony was that apart from a nebulous idea that Pakistan would include the Muslim majority parts of the North-west of India and East Bengal, there was no clarity on the territorial boundaries of such a nation state. For many Muslims, the notion of a Pakistan without Delhi was impossible to imagine. Afterall, the city boasted a 1000-year history of Muslim rulers and was the seat of numerous Sufi sects and an emotional bond for the pious. While the revolt of 1857 marked the death knell for Delhi as the centre for political Islam in India, the anxieties of partition and the possibility of Delhi integrating into Pakistan revived the city’s role as a contested geography for the two large communities of the city. Pakistan, in the imagination of its believers, included Delhi, Aligarh and in some instances a continuous tract of land connecting West and East Pakistan. Some of the weirder imaginations also included distant Hyderabad. During this period, Jinnah also moved to Delhi and took lodgings in a stately bungalow in Aurangzeb Road.

The bloody violence after the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 (specially in Calcutta) was the final writing on the wall that the Partition of the subcontinent would be impossible to not consider. When India finally gained Independence on 15th August, it was Delhi that ended up bearing the brunt of the impact. Professor Rotem Geva’s “Delhi Reborn: Partition and Nation Building in India’s Capital” is an eye-opening analysis of this period.

The riots that engulfed the city in September 1947 was nothing short of ethnic cleansing according to Prof Geva. The horrors of the journeys undertaken by millions across the border has been well-documented in literature and cinema (Manto, Khushwant Singh, Yashpal, Mira Nair, Aanchal Malhotra…); the rage and hatred of the refugee experience resulted in mayhem against the minorities of Delhi. Gandhi reached the city in the same month and decided to stay on until peace returned. He was never to leave the city again, being assassinated within 5 months. (The role of the RSS in providing relief to the incoming refugees even before the governments stepped in and their preparation for civil war right since the Calcutta killings are detailed out by Prof. Geva)

In September 1947, the city underwent an enormous demographic transformation: roughly 350,000 Muslims—about two-thirds of Delhi’s Muslim population—fled to Pakistan, while half a million Hindu and Sikh refugees settled in their place. Weapons left from the US forces that were stationed in Delhi flooded the black market and often rumours of Muslim localities possessing a stash of weapons were reason enough for the Home Department and Hindu refugees to lay siege to localities. The brunt of the violence was concentrated in localities such as Karol Bagh, Paharganj and Sadr Bazar.

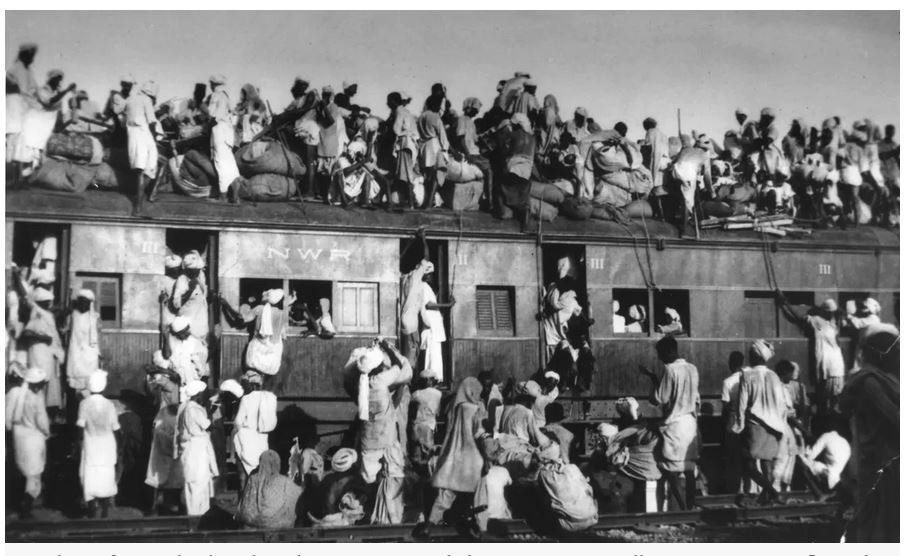

The riots drove the Muslims who survived out of their neighbourhoods, in search of safer places. Abdul Rahman Siddiqi recalls how the survivors from Phatak Habash Khan came trickling into his Muslim-majority locality of Ballimaran. Dehlvi witnessed his neighbourhood of Jama Masjid turning into an improvised refugee camp. Those who managed to flee the violence in the mixed localities stayed with their relatives and friends. Every house hosted a dozen or two dozen guests, and those who could not be accommodated spent their days and nights in the by lanes of the mohalla (neighbourhood). Jama Masjid’s population doubled within a few days. Congestion became unbearable and verged on hazardous, since there were no sanitary arrangements for cleaning. The mehtar (sweepers) stopped cleaning the mohalla, and cholera broke out. Other temporary refugee centers for Muslims were set up in Idgah (Sadar Bazar) and in a by-lane on Qutab Road (the main road running north-south through both Sadar Bazar and Paharganj). As these swelled with people, Muslim refugees were transferred to the two large refugee camps opened for them south of New Delhi, in the ruins of Humayun’s Tomb and the medieval fort Purana Qila, which served as an internment camp for Japanese during World War II. By mid-September, there were as many as 120,000 Muslim refugees in the camps, living in horrid conditions without sanitation. By late October most of them were evacuated by trains to Pakistan, while others—thousands according to some, hundreds according to others—returned to the city.

The large scale violence and migration from either side of the border gave rise to the phenomenon of Evacuee property. Properties evacuated by Muslims were entrusted to the custody of an official custodian who collected rent from the refugee tenants. (Muhammad Ali Jinnah himself sold his house on Aurangzeb Road to the Hindu businessman Ramkrishan Dalmia). However, the crumbling relationship with Pakistan and the large-scale animosity between refugee Hindus and Muslim tenants resulted in the system collapsing.

This horrid period should be a reference point to understand the concept of citizenship. What makes one a citizen of a land? I had written earlier of the idea of a nation as an imagined community. How does one reconcile oneself when one is geographically separated from her imagined community. The minorities in both India and Pakistan ended up having to reconcile their future in the newly created countries – a fact which got further solidified in the Nehru-Liaquat Pact of 1947. With the political leadership of the Muslim League evaporating after Independence, the onus was on the new political leadership of India and the nationalist Muslims (Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was the foremost representative of this voice) to build together a society that was torn apart by centuries of mistrust. Something, that is still on ongoing exercise playing out in our political and social lives even today.

Today, our Constitution guarantees our citizenship and protects the rights of all citizens. It’s pertinent to note that between August 15th 1947 and 26th January 1950, when much of the violence in Delhi unfolded, India was not a Constitutional republic, but a Dominion of the British Commonwealth.

Postscript: During independence, Pakistan yearned for not just for Kashmir but also Junagadh and Hyderabad. I’ll someday write about this but for now, Shekhar Gupta’s Cut the Clutter episode on this has a lot of historical context and also features a fantasy map of Pakistan.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Delhi during the Partition”