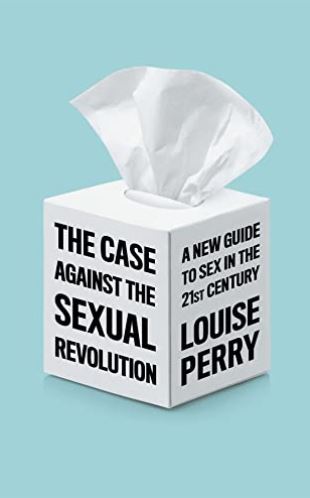

Feminism, like all isms, brooks no dissent. For this reason, Louise Perry’s argument against the sexual revolution, brought about and cheered largely by the feminist movement from the 60s, requires a wider reading. While I disagree with her conclusions, her courage to stick her neck out and make her arguments makes this an important addition to the canon of feminist literature.

For Perry, the invention of the pill in the 60s was the watershed moment that freed women from the risk of unwanted pregnancies and provided them the opportunity to engage in sex with ‘equal’ gusto as men. Perry’s main grouse is the feminist movement’s adoption of ‘choice’ as the fundamental arbiter to normalize this ‘freedom’. What most feminists miss in this argument has been the fact that the process of encouraging women to experience and experiment has been largely for the benefit of men. Perry’s arguments gain added credibility from her experience of working in a rape crisis center. For Perry, the refusal of modern feminists to accept that men are evolutionary wired to be aggressive, that rape victims are largely younger women and that victims need to be made aware of ‘safety’ behaviors without being categorized as ‘victim-blaming’ are all deeply problematic.

With the right tools, freedom from the constraints imposed by the female body now becomes increasingly possible. Don’t want to have children in your twenties or thirties? Freeze your eggs. Called away on a work trip postpartum? Fed-Ex your breastmilk to your newborn. Want to continue working fulltime without interruption? Employ a live-in nanny, or – better yet – a surrogate who can bear the child for you. And now, with the availability of sex reassignment medical technologies, even stepping out of your female body altogether has become an option. Liberal feminism promises women freedom – and when that promise comes up against the hard limits imposed by biology, then the ideology directs women to chip away at those limits through the use of money, technology and the bodies of poorer people. I don’t reject the desire for freedom… But I am critical of any ideology that fails to balance freedom against other values, and I’m also critical of the failure of liberal feminism to interrogate where our desire for a certain type of freedom comes from, too often referring back to a circular logic by which a woman’s choices are good because she desires them.

Taking on from this, Perry analyses the institution of marriage, the phenomenon of rape, the normalization of prostitution by feminists, the porn industry, the proliferation of BDSM and much more.

By drawing on from examples and anecdotes from extreme cases – teen girls drugged and raped repeatedly, women in abusive marriages, porn stars with traumatic experiences etc, she makes some real bleak recommendations– stay away from casual sex, stay off dating apps, invest in the institution of marriage, be choosy with the men you date, and so on. All good options for sure, but not something that I would preach as a one-size-fits-all option. I know, (heck, I know you too know) women who are promiscuous, active on dating apps, polygamous and also at the same time happy, loving parents, caring partners and wonderful human beings. Morality driven by one’s ethical framework can never be absolute. It’s subjective, driven by a person’s values and often a product of the times that we live in. The socio-economic and cultural milieu we find ourselves in, our peers, our religious beliefs, the law of the land and our conscience altogether get concocted to make our moral positions.

Do read the book. It’s an important reminder that theory has limited use when it comes to issues such as feminism. Like ethics, there can be no absolute positions.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sounds interesting now let mr go follow

LikeLike

By saying that feminism appeared on a particular day or started at so and so time period, one takes away the whole point of what the term could/should stand for. Feminism to me, is as old as the human condition. Because, for as long as history can find evidence, humans, have been fighting to better their conditions and have the right to make their own choices. Its only when a lot of women make similar choices at similar times does it get tagged into feminism. I think the lens should not be what women are wanting to choose for themselves but that if its fair to make your own choices for humanity as a whole, then why question 50% of that segment if they do so?

LikeLike