Most of the iconic structures of Bombay were built by the profits from the cotton trade. To understand this, one needs to grasp how cotton emerged as the key commodity driving imperialists, plantation owners and bankers for almost three hundred years. Columbus’ discovery of America and Vasco da Gama’s discovery of the sea route to India set the ball rolling for the emergence of cotton as the key commodity of global trade during this period.

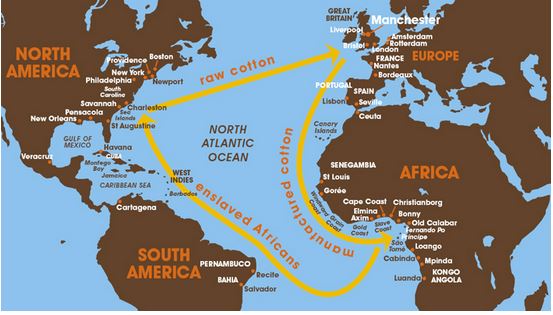

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, Indian textiles were picked up by European traders to pay for Southeast-Asian spices and to exchange them for slaves from Western Africa. The purchased slaves were then sent to the sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The huge demand for slaves in the Americas created pressure to secure more cotton cloth from India. When profits kept zooming, companies started scouting for new territories to grow cotton and spin them into yarn.

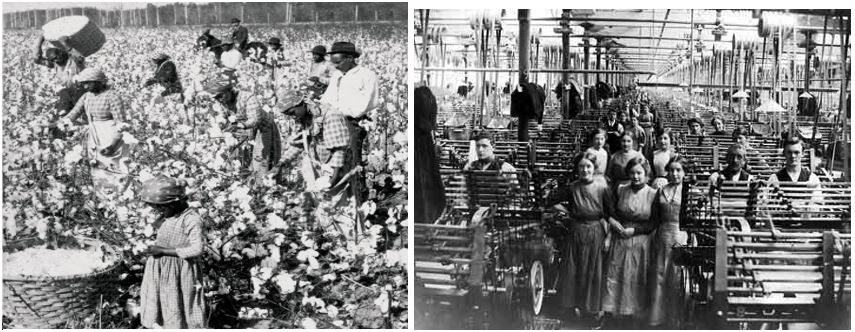

Until the early 18th century, cotton production was limited as most of the world’s cotton was grown by small farmers in Asia, Africa and Latin America. This situation changed with the explosion of plantation agriculture in America driven by slave labour. With land and labour no longer being a constraint, cotton production picked up. During the same time, the spinning jenny was invented in England heralding the Industrial Revolution. Within a few years, slave-grown American cotton began to be manufactured into yarn in Lancashire, which was later shipped to India to be woven into a shirt somewhere in the Indian countryside. The empire of cotton consisted of tens of thousands of such ties.

In 1861, the American Civil War upended this delicate balance. The South (Confederates) initially stopped all exports assuming that the tactic would make Britain immediately recognize their sovereignty. When this backfired, exports couldn’t be resumed due to the blockade enforced by the Union (the North). To capitalize on this, Indian traders ramped up production and, in a year, managed to corner 75% of the world’s cotton production. The extraordinary windfall got pumped into the construction of the buildings that today dot Bombay’s skyline.

It was in the backdrop of this global cotton trade, that Gandhi put forward his nostalgic vision of Indians spinning their own cloth. It’s not hard to see why the act of spinning had such an emotive impact. Also easy to now understand is why the movement never took off as a solution to rural distress. The global supply chains were too attractive for even Indian industrialists to not shun them.

Do check out Sven Beckert’s ‘Empire of Cotton‘ for a more detailed take on the issue.

Discover more from Manish Mohandas

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

5 thoughts on “The Empire of Cotton”